When a pharmacist hands you a pill bottle labeled with a generic name instead of the brand your doctor wrote on the prescription, they’re not just saving you money-they’re navigating a web of state and federal laws that could land them in legal trouble if done wrong. This isn’t about preference. It’s about compliance. And the rules vary dramatically from one state to the next.

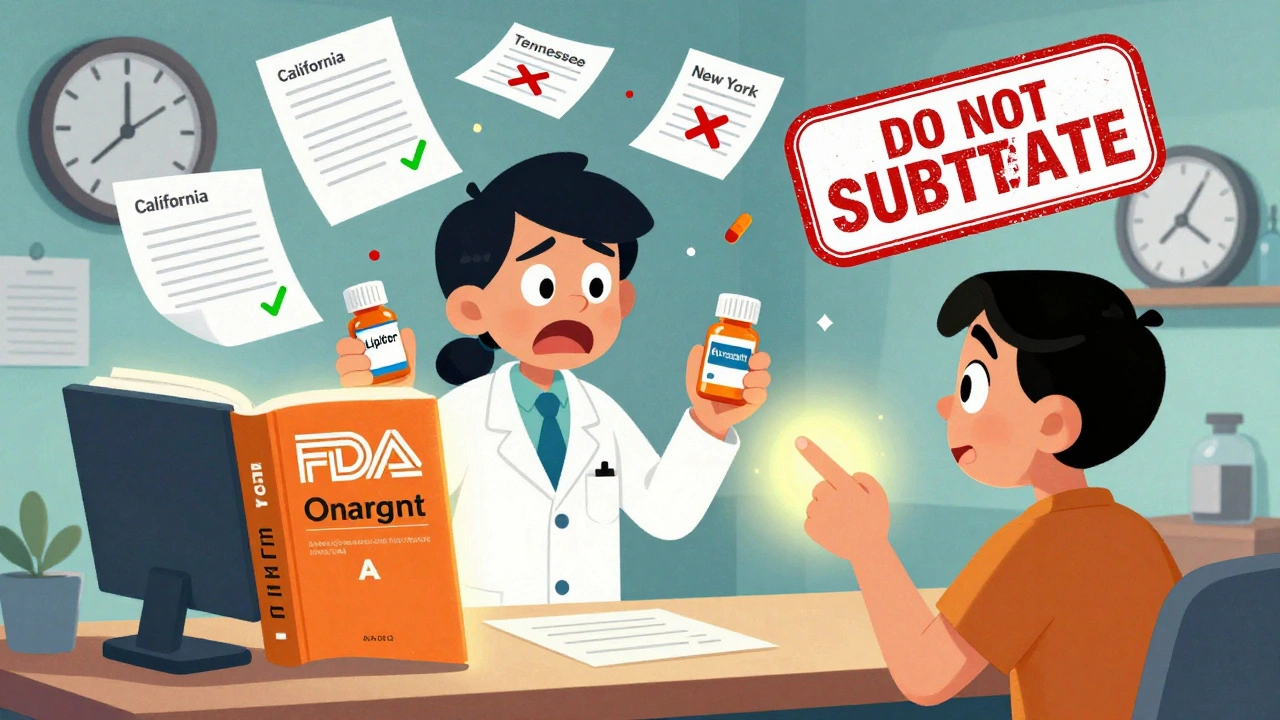

What You Can and Can’t Substitute

The FDA approves generic drugs based on strict bioequivalence standards. That means the active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and how the body absorbs the drug must match the brand-name version. The FDA Orange Book is the official list that tells pharmacists which generics are approved for substitution. If a drug isn’t rated as ‘A’ in the Orange Book, substitution is illegal-even if the names look similar.

But here’s the catch: not all A-rated drugs can be swapped. Certain categories are off-limits in many states. Antiepileptic drugs like phenytoin, anticoagulants like warfarin, cardiac glycosides like digoxin, and thyroid medications like levothyroxine are often excluded because small changes in blood levels can cause serious harm. In Tennessee, substituting any antiepileptic drug for a patient with epilepsy is strictly forbidden, regardless of FDA rating. Hawaii requires explicit consent from both the doctor and patient before swapping any epilepsy medication. California bans substitution for levothyroxine unless the prescriber checks a box saying it’s okay.

Mandatory vs. Permissive Substitution Laws

There are 24 states where pharmacists must substitute a generic unless the doctor says ‘do not substitute’ or the patient refuses. These are called mandatory substitution states. New York and California are among them. In these places, if you pick up a prescription for Lipitor and a generic atorvastatin is available, the pharmacist has to give you the cheaper version-unless you or your doctor block it.

In the other 26 states, substitution is optional. These are permissive substitution states. Pharmacists can choose to swap, but they’re not required to. This gives them more room to use professional judgment. For example, if a patient has had bad reactions to a particular generic brand before, the pharmacist can stick with the brand-even if it costs more.

Consent Rules: Presumed vs. Explicit

Even if substitution is allowed, the law says how you must get permission. In 18 states, consent is presumed. That means the pharmacist can switch the drug without asking, unless the patient says no. In 32 states, consent must be explicit. The pharmacist must tell you the brand is being changed, explain why, and get your verbal or written okay before handing over the pills.

And it’s not just about saying ‘yes.’ In states like Florida and New Jersey, pharmacists must document this consent in writing-either on the prescription, in the pharmacy’s electronic record, or on a separate form. Failing to do so is a violation, even if the patient didn’t object. One pharmacist in Ohio lost their license in 2022 after a patient suffered a seizure because their antiepileptic drug was swapped without documented consent.

The ‘Medically Necessary’ Rule

Doctors can stop substitution by writing ‘medically necessary’ on the prescription. But how they do it matters. In Florida, the phrase must be handwritten on paper prescriptions. For electronic prescriptions, the prescriber must select a specific checkbox in the e-prescribing system. If they just type ‘medically necessary’ in the notes section, it doesn’t count. In some states, the doctor must also initial the note.

Pharmacists are expected to check for this every time. A 2023 audit by the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy found that 41% of pharmacists in permissive states failed to verify whether ‘medically necessary’ was properly documented. That’s a major risk. If a pharmacist substitutes anyway, they’re on the hook-even if the doctor made the mistake.

Documentation Is Your Shield

Most disciplinary actions against pharmacists aren’t about giving the wrong drug. They’re about not writing things down. According to NASPA data, 68% of substitution-related violations in 2022 were due to poor documentation. That means no record of patient consent, no note about the ‘medically necessary’ designation, or no log of the generic product’s lot number.

Every time you substitute, you need to record:

- The name of the generic dispensed

- The brand name it replaced

- Whether the patient was notified

- Whether consent was obtained and how

- Whether the prescriber indicated ‘medically necessary’

- The FDA Orange Book rating of the generic

Electronic systems can auto-fill some of this, but many pharmacies still use paper logs or outdated software. Pharmacist Sarah Chen, who’s worked in California for 15 years, says, ‘I’ve seen too many cases where the system says ‘consent obtained,’ but there’s no signature, no timestamp, no note. That’s not enough.’

What Happens When You Get It Wrong

Violating substitution laws can mean fines, mandatory training, suspension, or even losing your license. In 2021, a pharmacist in Oklahoma was fined $10,000 and put on probation after substituting a generic anticoagulant without consent. The patient had a dangerous bleed. The pharmacy chain paid an additional $1.2 million in settlement.

It’s not just about patient safety. Insurance companies and state Medicaid programs audit pharmacies for substitution compliance. If they find patterns of improper swaps, they can cut reimbursement rates or drop the pharmacy from their network.

Staying Current Is Non-Negotiable

State laws change. In 2022 alone, 17 states updated their generic substitution rules. Tennessee added new restrictions on insulin. Florida expanded its list of excluded drugs. New York changed its consent requirements for controlled substances.

There’s no single federal database that tracks all these changes. Pharmacists must monitor their state board of pharmacy website, subscribe to alerts from the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP), and attend continuing education sessions. The NABP estimates pharmacists need 40-60 hours of training per year just to keep up with substitution laws.

Biosimilars and the Future

It’s not just about pills anymore. Biosimilars-generic versions of complex biologic drugs like Humira or Enbrel-are now entering the market. Thirty-two states have passed laws governing their substitution, but the rules are even stricter. Unlike small-molecule generics, biosimilars aren’t automatically interchangeable. Pharmacists must confirm the product is FDA-designated as ‘interchangeable’ and get prescriber consent before switching.

The FDA is also updating labeling requirements for all generics. By the end of 2024, every generic bottle must include a clear statement like: ‘This product is a generic version of [brand name]. It is approved as safe and effective.’ This is meant to reduce confusion, but it also adds another layer of compliance for pharmacists.

Bottom Line: Your Job Is More Than Filling Bottles

Dispensing generics isn’t a simple cost-saving task. It’s a legal and clinical responsibility. You’re the last line of defense between a patient and a potentially dangerous substitution. You need to know the law, document everything, and never assume. Even if a drug is A-rated, even if the patient says ‘it’s fine,’ even if the system auto-checks ‘consent’-you still have to verify.

The system works because pharmacists do their job right. But one mistake, one skipped step, one undocumented consent can change a life. And the law won’t care if you were ‘just busy.’

Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness

Ollie Newland

December 4, 2025 AT 15:16Man, I’ve seen pharmacists get tripped up on this stuff all the time. One guy in Manchester just swapped my warfarin because the system auto-checked ‘consent’-no talk, no signature. I had to go back two days later because my INR went through the roof. Documentation isn’t bureaucracy-it’s your only shield when things go sideways.

Bill Wolfe

December 5, 2025 AT 16:48It’s frankly astonishing how many pharmacists treat this like a vending machine operation. The FDA Orange Book? A mere footnote. Consent protocols? An inconvenience. And yet, we’re expected to trust them with life-altering meds. This isn’t ‘cost-saving’-it’s regulatory roulette, and the stakes are your kidneys, your heart, your brain. If you’re not documenting every swap like it’s a court deposition, you’re not a pharmacist-you’re a liability with a white coat.

Rebecca Braatz

December 6, 2025 AT 08:15Hey everyone-this is SO important. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen patients get hospitalized because a generic was swapped without consent. Don’t let the system make you lazy. Ask. Document. Double-check. Even if it takes 90 extra seconds. That’s the difference between ‘I did my job’ and ‘I almost killed someone.’ You’re not just filling scripts-you’re holding someone’s life in your hands. Be proud of that. And if your pharmacy won’t let you do it right? Speak up. We need more of you.

zac grant

December 7, 2025 AT 17:04Real talk: I’ve worked in 3 states and the variation is insane. In Texas, they’ll swap levothyroxine like it’s aspirin. In California, you need a signed waiver, a notary, and a blood oath. The NABP alerts are gold-subscribe to them. Also, biosimilars? Big looming mess. Interchangeable ≠ substitutable. If your EHR doesn’t flag that, you’re flying blind. Pro tip: print the FDA’s interchangeability list and tape it to your counter. No excuses.

jagdish kumar

December 8, 2025 AT 17:59We are all just atoms in a machine… and the machine forgets to ask.

Benjamin Sedler

December 10, 2025 AT 08:58Wait, so if a pharmacist swaps my ADHD med because the system auto-checked ‘consent’ but I didn’t even know I was getting a generic… is that illegal? Or just… weirdly American? Like, why are we trusting a computer to decide whether my brain chemistry gets tweaked by a 3% difference in filler? I don’t even trust my phone to send a text without autocorrect ruining it. How is this legal?

michael booth

December 11, 2025 AT 07:02Pharmacists are the unsung guardians of medication safety. The level of diligence required to comply with state-by-state substitution laws is extraordinary. Every signature every timestamp every note is not paperwork-it is protection. For patients. For practitioners. For the integrity of the profession. I salute those who do it right every single day.

Carolyn Ford

December 11, 2025 AT 19:47Oh, please. ‘Document everything’? That’s just corporate cover-your-ass nonsense. Real pharmacists know their patients. If Mrs. Johnson has been taking atorvastatin for 12 years and says ‘just give me the generic,’ why are we making her sign a 7-page form? It’s patronizing. And don’t get me started on ‘medically necessary’-if the doctor didn’t write it clearly, that’s their fault, not mine. Stop punishing the people trying to save people money.

Heidi Thomas

December 12, 2025 AT 09:12Anyone who thinks this is complicated hasn’t worked in a pharmacy. It’s simple: if the doctor didn’t say no, you swap. If the patient didn’t say no, you swap. If the system says consent was given, you swap. Stop overcomplicating it. The FDA says it’s safe. The law says you can. So do it. The rest is noise.

Michael Feldstein

December 13, 2025 AT 17:21Love this breakdown. One thing I’d add: if you’re in a permissive state and you’re not sure whether a prescriber meant ‘medically necessary’ in the notes, CALL THEM. I’ve done it a dozen times. Most docs are happy to clarify. And if they’re not? That’s your red flag. You’re not being annoying-you’re being the last line of defense. Also, shoutout to Sarah Chen. She’s right. Auto-checks aren’t consent. A timestamp without a signature is just a ghost.