What Palliative and Hospice Care Really Mean

Palliative care isn’t just for people who are dying. It’s for anyone living with a serious illness-cancer, heart failure, COPD, dementia-and struggling with pain, nausea, breathlessness, or anxiety. The goal? To make life as comfortable as possible, no matter how long someone has left. Hospice care is a type of palliative care, but it’s specifically for those with a prognosis of six months or less who’ve decided to stop curative treatments. Both focus on quality of life, not curing disease.

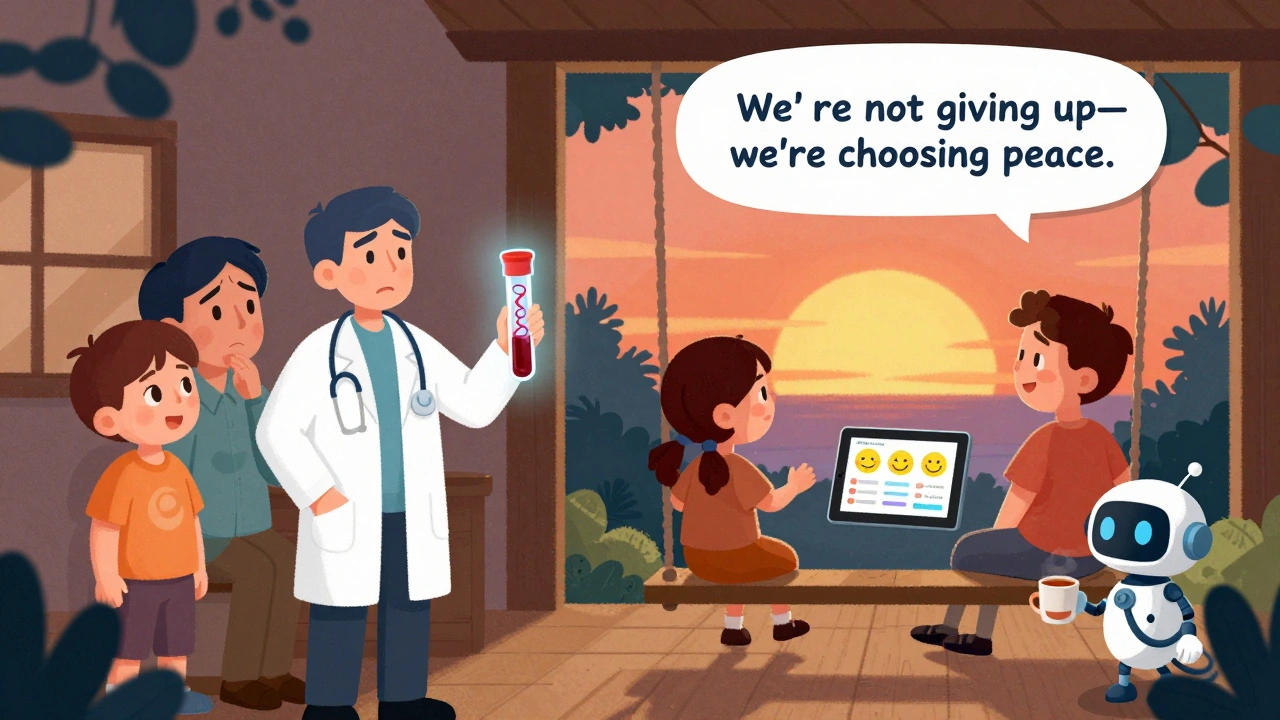

Many people think hospice means giving up. It doesn’t. It means choosing comfort over more hospital visits, more scans, more drugs that don’t help much but make you feel worse. The palliative care is a specialized medical approach focused on relieving suffering from serious illness, including physical, emotional, and spiritual distress, for patients and families team doesn’t just hand out pills. They listen. They adjust. They watch for side effects like drowsiness, confusion, or constipation-and fix them before they become bigger problems.

How Doctors Measure Pain and Other Symptoms

Not all pain is the same. A sharp stabbing pain in the ribs isn’t treated like a dull ache in the lower back. That’s why skilled palliative teams use detailed tools. The NHS North West guidelines require clinicians to document pain location, type, intensity (on a 0-10 scale), what makes it worse or better, and how it affects daily life. A patient might say, "My pain is a 7," but if they can’t walk to the bathroom or sleep through the night, that’s a different story than someone who’s just uncomfortable.

For breathlessness, opioids like morphine are the go-to. Evidence shows they work-even if the patient doesn’t have cancer. For anxiety or agitation, lorazepam is often used in small doses, checked every 30 minutes until the person is calm. Delirium? That’s tracked with tools like CAM-ICU and RASS scores every few hours. If someone’s confused or restless, haloperidol might be given, but only if it’s truly needed-and stopped as soon as the person settles down.

The Fine Line Between Relief and Over-Sedation

The biggest fear in palliative care isn’t that the patient will suffer. It’s that they’ll be so heavily medicated they can’t talk to their family, watch the sunset, or hold a grandchild’s hand. That’s why titration matters. Medications are started low and increased slowly. A nurse might give 2 mg of morphine, wait an hour, then check: Are they breathing okay? Are they alert enough to answer a question? If yes, they wait. If not, they adjust.

One study showed that when assessments were done every 30 minutes for patients in distress, breakthrough symptoms dropped by over half. But when staff skipped checks because they were busy, over-sedation spiked. The same thing happens with laxatives. Too little, and constipation turns into a medical emergency. Too much, and the patient gets cramps or diarrhea. It’s a tightrope walk.

Doctors don’t just guess. They use guidelines like those from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute provides modular, symptom-specific protocols including separate guides for pain (Pink Book) and nausea (Green Book). These aren’t rigid rules-they’re starting points. A 78-year-old with kidney disease needs different doses than a 45-year-old. That’s why experience matters.

Non-Drug Tools That Actually Work

Medication isn’t the only answer. Sometimes, the best fix is something simple. A cool cloth on the forehead for nausea. A quiet room with dim lights for someone with delirium. A fan blowing gently across the face for breathlessness. Music therapy. Holding hands. Talking about memories.

A 2023 update from Fraser Health added guidance on cannabinoid therapy, showing it can reduce opioid use by 37% in some patients, though it can cause dizziness. That’s not a magic bullet, but it’s another option. And it’s not just about drugs anymore. The NCHPC guidelines outline 8 domains of care, including psychological, social, and spiritual support-not just pills. One patient might need a chaplain. Another might need help talking to their kids about death. These aren’t "extras." They’re part of the treatment plan.

Why Families Resist-and How to Help

One of the hardest parts isn’t medical. It’s emotional. Families often think, "If we give more pain medicine, we’re killing them." That’s not true. Giving enough morphine to stop pain doesn’t speed up death. It lets the person be present. But changing that belief takes time.

Teams use clear language: "We’re not trying to make them sleepy. We’re trying to make them comfortable so they can talk to you." They show families the pain scale. They explain that untreated pain can cause more harm than the medicine. Sometimes, they bring in someone who’s been through it-a former patient’s spouse, or a volunteer who’s lost a loved one.

And documentation helps. When nurses write down exactly when a dose was given and how the patient responded, families see the care is intentional, not random. That builds trust.

What Happens When Care Is Delayed

Too many patients wait until they’re in the ER to get palliative care. By then, they’ve had months of uncontrolled pain, nausea, and anxiety. The body is worn down. The family is exhausted. The chance to have peaceful days at home is gone.

Research shows that people who start palliative care early-alongside their cancer treatment or heart failure meds-live longer and feel better. One landmark study in the New England Journal of Medicine found patients with lung cancer who got early palliative care lived 3.2 months longer and had fewer hospital stays.

Delaying care doesn’t make sense. It’s like waiting until your car is smoking before you change the oil. The system is catching up-96% of big U.S. hospitals now have palliative teams. But in rural areas, 55% of counties still have no access. That’s where telehealth is stepping in. Video visits for symptom checks are growing fast.

What’s Changing in 2025

The field is evolving. The NCHPC is preparing its 5th edition of Clinical Practice Guidelines, launching in 2025, with new focus on digital symptom tracking tools. Patients using apps to report pain or nausea in real time have seen an 18% improvement in control. That means faster adjustments, fewer crises.

Also, research is uncovering genetic differences in how people respond to opioids. Some people need 10 times more morphine than others. A simple blood test might soon tell doctors what dose to start with-cutting trial-and-error.

And the workforce? There are only 7,000 certified palliative doctors in the U.S., but over 22,000 needed. Training more nurses, social workers, and chaplains is now a national priority. The NIH is spending $47 million on non-drug approaches-like mindfulness, acupuncture, and massage-to reduce reliance on pills.

How to Get Started

If you or someone you love has a serious illness and isn’t feeling well, ask: "Can we get palliative care?" You don’t need a referral from a specialist. Talk to your doctor. Ask your hospital. Call your local hospice. Most offer free consultations.

Start with the basics:

- Use a 0-10 scale to rate pain, nausea, or breathlessness every day.

- Write down what helps-ice packs? Sitting up? A favorite song?

- Ask about side effects: "Will this make me drowsy? Constipated? Confused?"

- Don’t wait until things get bad. Call for help early.

There’s no shame in wanting comfort. There’s no failure in choosing peace. And there’s no rule that says you have to suffer to be brave.

Is hospice care only for cancer patients?

No. Hospice care is for anyone with a terminal illness and a prognosis of six months or less, regardless of diagnosis. This includes heart failure, advanced dementia, COPD, ALS, liver disease, and more. The focus is on comfort, not the type of illness.

Does using morphine mean I’m close to death?

Not at all. Morphine is used to relieve pain and breathlessness, not to end life. Many patients live for weeks or months on morphine and feel much better. The dose is adjusted to the person’s needs-not their timeline. It’s about comfort, not countdowns.

Can I still get chemotherapy or other treatments while on palliative care?

Yes. Palliative care can be given at the same time as curative treatments like chemotherapy, dialysis, or surgery. It’s not either/or. Many patients get both: treatment to slow the disease, plus palliative care to manage side effects like nausea, fatigue, or pain.

What if my family doesn’t want me to take pain meds?

It’s common for families to fear addiction or overdose. Palliative teams explain that addiction is rare in patients using opioids for pain. They also show how uncontrolled pain causes stress, sleeplessness, and even faster decline. A social worker or chaplain can help talk through fears and values so everyone understands the goal: comfort and dignity.

How do I know if it’s time for hospice?

Signs include frequent hospital visits, weight loss, fatigue that doesn’t improve, needing help with daily tasks like bathing or eating, and a doctor saying curative treatments won’t change the outcome. If you’re asking this question, it’s worth having a conversation with your doctor about hospice as an option-not a last resort, but a better way to live the time you have.

Final Thought: It’s About Living, Not Just Ending

Palliative and hospice care aren’t about giving up. They’re about choosing how you want to live-with less pain, more presence, and more moments that matter. Whether it’s hearing your grandchild laugh, watching the sunrise from your bed, or just being held without hurting-those moments are worth fighting for. And they’re possible, even at the end.

Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness

Donna Anderson

December 11, 2025 AT 23:34Audrey Crothers

December 13, 2025 AT 22:30Adam Everitt

December 15, 2025 AT 00:52Rob Purvis

December 16, 2025 AT 19:25Ashley Skipp

December 16, 2025 AT 21:35Nathan Fatal

December 17, 2025 AT 05:27wendy b

December 18, 2025 AT 22:29Laura Weemering

December 19, 2025 AT 07:36Stacy Foster

December 21, 2025 AT 04:45Reshma Sinha

December 22, 2025 AT 02:23sandeep sanigarapu

December 23, 2025 AT 18:43nikki yamashita

December 24, 2025 AT 05:48Lawrence Armstrong

December 25, 2025 AT 01:15Robert Webb

December 25, 2025 AT 07:11Levi Cooper

December 26, 2025 AT 11:42