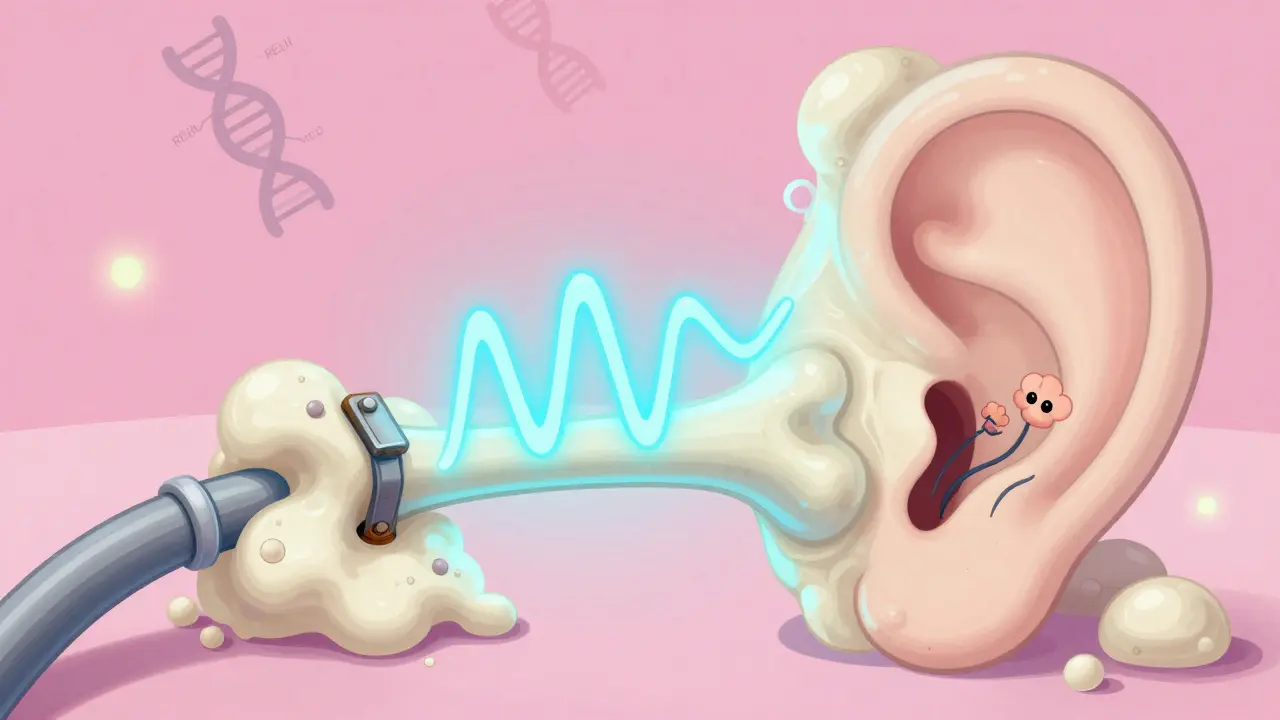

Imagine sitting across from your partner, watching their lips move, but hearing only muffled sounds. You keep saying, "What?" - not because they're speaking softly, but because your own ears aren't picking up low tones anymore. This isn't just aging. It could be otosclerosis, a quiet but progressive condition where abnormal bone grows in the middle ear and locks up the tiny stapes bone, blocking sound from reaching the inner ear.

What Exactly Is Otosclerosis?

Otosclerosis is not a tumor or infection. It's a bone remodeling problem. Normally, bones in your body renew themselves slowly and evenly. In otosclerosis, the bone around the stapes - the smallest bone in your body, just 3.2mm long - starts growing in a messy, irregular way. Instead of staying smooth and mobile, it becomes spongy at first, then hardens and fuses to the oval window, the doorway to your inner ear. When that happens, the stapes can't vibrate. Sound waves get stuck. You lose the ability to hear low-pitched sounds clearly - whispers, bass tones, a man's voice across the room. This condition doesn't strike suddenly. It creeps in over years. Most people notice it between ages 30 and 50. Women are more likely to develop it, especially during pregnancy, when hormonal changes can speed up the bone growth. About 70% of cases occur in women, and 60% of those affected have a family member with the same issue. Genetics play a big role. Researchers have identified at least 15 gene locations linked to otosclerosis, with the RELN gene on chromosome 7 being the strongest predictor.How Do You Know You Have It?

The first sign is usually trouble hearing low sounds. People often think their spouse is mumbling. Or they can't hear the TV unless it's loud - but even then, voices sound unclear. High-pitched sounds, like children's voices or birds chirping, might still come through fine. That’s different from age-related hearing loss, which usually starts with high frequencies. Another common symptom is tinnitus - a ringing, buzzing, or hissing in the ear. Around 80% of people with otosclerosis report tinnitus, and for 35% of them, it’s bad enough to disrupt sleep. The only way to confirm it is through a hearing test called pure-tone audiometry. A typical result shows an air-bone gap - meaning sound travels poorly through the air of the ear canal to the inner ear, but bone conduction (sound sent directly through the skull) works better. An air-bone gap of 20-40 dB is common. If your speech discrimination score is still above 70%, that’s another clue it’s otosclerosis and not nerve damage.Why It’s Not Just “Getting Older”

Many people assume hearing loss is just part of aging. But otosclerosis is different from presbycusis (age-related hearing loss). Presbycusis usually starts after 65 and hits high frequencies first. Otosclerosis hits younger adults, often in their 30s and 40s, and targets low frequencies. It also doesn’t come and go like Meniere’s disease, which causes sudden vertigo and fluctuating hearing. It’s also not Eustachian tube dysfunction, which can cause pressure and muffled hearing but usually improves with decongestants or yawning. Otosclerosis doesn’t change with colds or allergies. That’s why many people wait an average of 18 months before getting the right diagnosis - often mislabeled as something temporary.

What Happens If You Don’t Treat It?

Left alone, otosclerosis slowly gets worse. On average, untreated cases lose 0.5 to 1.0 dB of hearing per year. Over five years, that adds up to a 15-20 dB drop - enough to make conversations in noisy rooms impossible. In about 10-15% of cases, the bone growth spreads into the cochlea, damaging the inner ear’s hair cells. That turns conductive hearing loss into mixed hearing loss - harder to fix. It rarely leads to total deafness. But it can steal your ability to hear your kids, enjoy music, or even follow a conversation in a quiet room. The emotional toll is real. People report feeling isolated, frustrated, or embarrassed when they keep asking people to repeat themselves.Treatment Options: Hearing Aids or Surgery?

There are two main paths: amplification or surgery. Hearing aids are the first step for many. They’re non-invasive, reversible, and effective. About 65% of people start here. Modern digital aids can be programmed to boost low frequencies specifically - exactly what otosclerosis steals. They don’t fix the bone growth, but they compensate for it. Many people live perfectly well with hearing aids for years. Surgery - specifically stapedotomy - is the only way to reverse the problem. In this procedure, the fixed stapes is partially removed and replaced with a tiny prosthetic (often made of titanium or platinum). A laser or micro-drill creates a small hole in the footplate, and the prosthesis is attached to the incus bone. Sound can then travel again. Success rates are high. About 90-95% of first-time stapedotomies restore hearing to within 10 dB of normal. The American Academy of Otolaryngology gives this procedure the highest evidence rating (Level A). Most patients notice improvement within weeks. One 45-year-old teacher in Tampa reported she could finally hear students whispering in the back row after surgery. But surgery isn’t risk-free. About 1% of patients experience sudden, permanent sensorineural hearing loss - a devastating but rare outcome. That’s why informed consent is critical. Surgeons must explain this risk clearly. Revision surgeries (if the first one fails) have lower success rates - around 75% - so getting it right the first time matters.New Developments in Treatment

In March 2024, the FDA approved a new prosthesis called StapesSound™. It’s coated with titanium-nitride, which reduces scarring and adhesions after surgery. Early trials show a 94% success rate at 12 months, up from 89% with older models. There’s also promising drug research. Sodium fluoride, a mineral used in toothpaste and osteoporosis treatment, has shown it can slow bone growth in the ear. A 2024 study found patients taking it had 37% less hearing decline over two years compared to those on placebo. It’s not a cure, but it might delay the need for surgery. Scientists are also working on genetic screening. Within five years, doctors may be able to identify high-risk individuals - even before symptoms appear - using polygenic risk scores. That could mean earlier monitoring and faster intervention.

Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness

Paul Huppert

December 30, 2025 AT 19:58Had this diagnosed last year. Thought my wife was just tired of talking to me. Turned out my audiogram looked like a mountain range. Hearing aids changed everything. Now I hear my dog bark again. Who knew?

Best $800 I ever spent.

Hanna Spittel

December 30, 2025 AT 23:38OMG I KNEW IT 😤

They’re hiding this from us. The FDA approved that new prosthesis right after Big Pharma bought the patent. You think they want you to hear better? Nah. They want you to keep buying hearing aids forever. 🤡

Brady K.

December 31, 2025 AT 01:09Let’s be real - otosclerosis isn’t a medical condition, it’s a capitalist feedback loop. We’ve turned human biology into a subscription service: hear worse → buy aids → get surgery → pay for revision → get scarring → repeat.

Meanwhile, sodium fluoride costs $12 a bottle and works better than half the devices on the market. But hey, why fix the system when you can sell a $12,000 titanium nail?

Also, ‘Level A evidence’? That’s just fancy talk for ‘we did one study in 2003 and haven’t looked back since.’

Joy Nickles

December 31, 2025 AT 23:25i had this too!! and i swear the doctor was like ‘oh its just aging’ and i was like no i’m only 34 and my mom has it too and then i found out it was otosclerosis and now i’m on sodium fluoride and honestly i think it’s working?? but i also think my cat’s purring helped?? idk just saying

also the stapedotomy scar looks like a tiny moon crescent and i’m weirdly proud of it??

Emma Hooper

January 2, 2026 AT 16:43Y’all are making this sound like some boring textbook. This is the plot of a Netflix drama. Picture it: woman in her 30s, whispers turn to silence, husband starts cheating because he thinks she’s ignoring him, turns out she can’t hear him say ‘I love you’ - because the bone in her ear is literally growing a tiny fortress.

And then - BAM - titanium prosthesis. Tears. Hugs. A Spotify playlist called ‘Hear Me Now’ drops. The end.

Also, if you’re reading this and you’re 42 and your mom had this - go get tested. NOW. Don’t wait until you miss your kid’s first word. I’m not crying, you’re crying.

Martin Viau

January 3, 2026 AT 14:26Why are Americans so obsessed with titanium implants? In Canada, we just use copper wire and prayer. Also, your ‘Level A evidence’? That’s just American hype. We’ve been treating this with saltwater rinses since the 70s. You people need to chill.

And why is every study funded by hearing aid companies? Suspicious.

Marilyn Ferrera

January 5, 2026 AT 10:31For anyone reading this - if you’re worried about hearing loss, don’t wait. Don’t Google it for 6 months. Don’t blame your partner. Go to the audiologist. Get the air-bone gap test. It takes 20 minutes. It could change your life.

And if your doctor says ‘it’s just aging’ - find a new doctor. That’s not medicine. That’s negligence.

Harriet Hollingsworth

January 7, 2026 AT 06:31People who get surgery are just giving up. You’re choosing to cut into your body instead of accepting that maybe you just need to listen better. Also, why are we normalizing invasive procedures for something that might be emotional? Maybe you’re just avoiding conversations. Maybe you don’t want to hear the truth.

And what about the 1% who go deaf after surgery? That’s not a risk. That’s a moral failure.

Frank SSS

January 7, 2026 AT 13:37Wait, so you’re telling me I’ve been yelling at my girlfriend because I thought she was being passive-aggressive… but I couldn’t hear her low voice the whole time?

That’s… actually kind of tragic.

Also, I just realized my dog stopped barking at me last year. I thought he was being lazy. Turns out, he was just tired of me not hearing him.

anggit marga

January 8, 2026 AT 11:41Why are you all talking about American medicine like it’s the only option? In Nigeria we use herbs and ancestral chants. My cousin’s uncle lost his hearing at 30 and now he hears better than before after 3 months of bitter leaf tea and drumming at sunrise. You think titanium is magic? Try the spirit world.

Also, your ‘FDA approved’ is just colonialism with a stethoscope.

Robb Rice

January 10, 2026 AT 06:00Just wanted to say - if you’re reading this and you’re scared, you’re not alone. I had surgery last year. I was terrified. I cried before the procedure. But I woke up and heard my daughter say ‘Daddy’ for the first time in years.

It’s not perfect. But it’s better. And that’s enough.

Deepika D

January 11, 2026 AT 15:45Hey everyone - I’m a hearing specialist and I’ve worked with over 300 otosclerosis patients. Let me say this clearly: hearing aids are not a backup. They’re a bridge. Surgery isn’t a last resort - it’s a reset button. And sodium fluoride? It’s not a cure, but it’s a pause button. You don’t have to choose one. You can do all three - and many of us do.

Also - if you’re young and you have a family history? Get screened now. Even if you feel fine. Genetics don’t wait. Your ears won’t warn you. You have to be the one to ask.

And if you’re feeling isolated? Join a group. Talk to someone. You’re not broken. You’re just hearing differently. And that’s okay. In fact - it’s beautiful. You’re learning to listen in a whole new way.

And yes - your kids will still love you even if you can’t hear them whispering. But wouldn’t you rather hear them?

Also - I’m happy to answer any questions. Seriously. DM me. No judgment. We’ve all been there.

Brandon Boyd

January 13, 2026 AT 03:04Look - I was skeptical too. Thought hearing aids were for grandpas. Then I got mine. Now I hear birds. Real birds. Outside my window. I didn’t even know they sang in C# minor.

Also - my wife started humming again. Turns out she sings in the shower. I just couldn’t hear it before.

Don’t wait. Just go.

Branden Temew

January 13, 2026 AT 22:14So… we’re spending millions on titanium implants and FDA-approved prostheses… but the real solution is fluoride toothpaste?

That’s the punchline to the universe’s worst joke.

Also - if you’re still using ‘Level A evidence’ as a justification, you’re not a doctor. You’re a marketing intern.