Every year, thousands of opioid pills sit untouched in medicine cabinets across homes - not because they’re needed, but because they’re no longer used. These leftover pills aren’t just clutter. They’re a silent threat. In 2021, over 107,000 people in the U.S. died from drug overdoses, and nearly 70% of misused prescription opioids came from friends or family members’ unused meds. If you’ve been prescribed opioids for pain after surgery, an injury, or chronic illness, you’re not alone. But what you do with the leftover pills matters more than you think.

Why Proper Opioid Disposal Matters

Opioids like oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, and fentanyl are powerful painkillers. They work - but they’re also highly addictive. When left in plain sight, they’re easy targets for teens, visitors, or even pets. A 2019 national survey found that most people who misuse prescription opioids get them from someone else’s medicine cabinet. That’s not theft. It’s access. And it’s preventable. The CDC calls safe disposal a Tier 1 prevention strategy. That means it’s one of the most effective ways to stop overdoses before they start. Studies show that when people dispose of unused opioids properly, diversion drops by up to 82%. In communities with strong disposal programs, opioid-related deaths have fallen by as much as 37%.Four Safe Ways to Dispose of Unused Opioids

There are four proven, approved methods to get rid of unused opioids. Not all are equally easy, but each has a place - especially if you live in a rural area or don’t have easy access to a drop-off site.1. Use a Drug Take-Back Program

This is the gold standard. Take-back programs collect unused medications and destroy them safely through high-temperature incineration. No chemicals. No pollution. Just complete destruction. The DEA runs National Prescription Drug Take Back Days twice a year, but you don’t need to wait. There are over 16,900 permanent collection sites across the U.S. These include:- Pharmacies (over 12,000 locations, including Walgreens and Walmart)

- Police stations and sheriff’s offices

- Hospitals and clinics

2. Use a Deactivation Pouch (Like Deterra or SUDS)

If there’s no take-back site nearby, deactivation pouches are your next best option. These are small, biodegradable pouches you buy at pharmacies. Inside: activated carbon and other compounds that neutralize opioids within 30 minutes. Here’s how to use them:- Remove pills from original bottle.

- Place pills and patches into the pouch.

- Add warm water (usually 1/4 to 1/2 cup, check the label).

- Seal the pouch and shake for 10 seconds.

- Throw it in the trash.

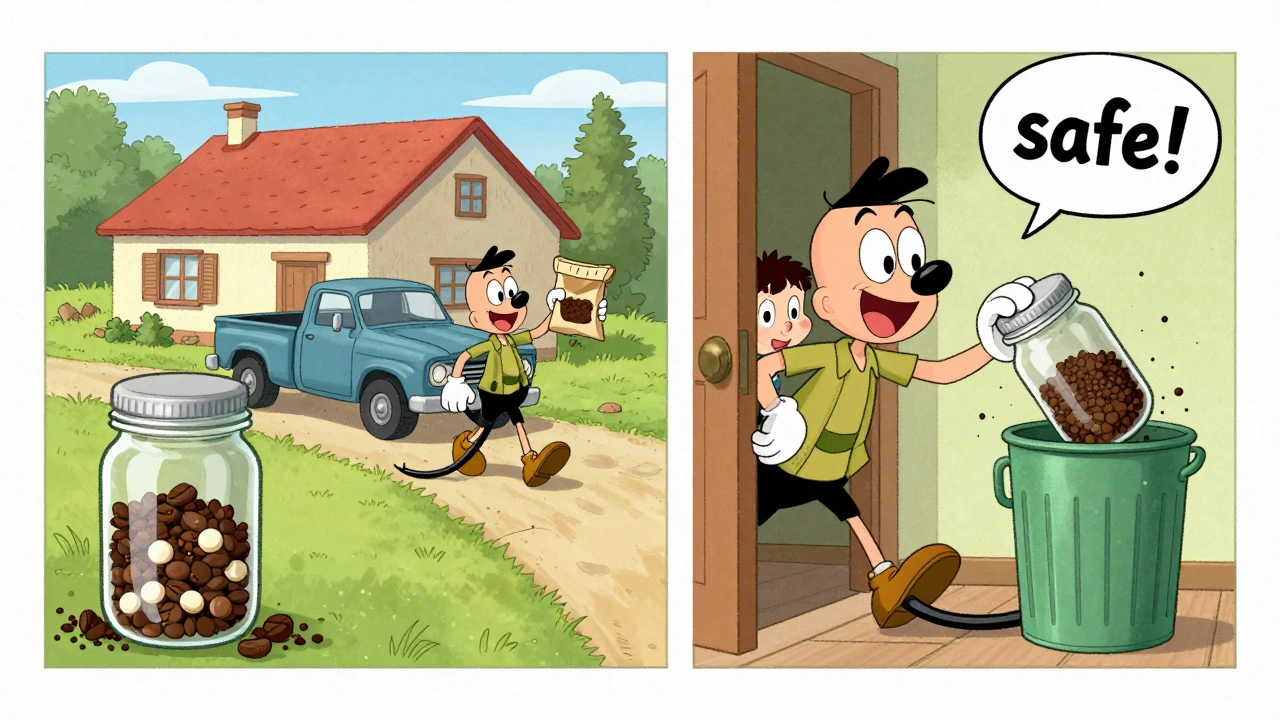

3. Household Disposal (FDA-Approved Method)

If you can’t get a take-back pouch or find a drop-off site, this method works - if done right. The FDA says you can dispose of most opioids at home by:- Removing pills from their original container.

- Mixing them with an unappetizing substance like used coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt.

- Putting the mixture into a sealed plastic bag or container (like a jar or empty detergent bottle).

- Covering or scratching out your name and prescription info on the empty bottle with a permanent marker.

- Throwing the sealed container in the trash.

4. Flush Only If Listed on the FDA Flush List

Flushing is controversial - and only recommended for a very short list of high-risk opioids. Why? Because flushing can contaminate water supplies. But for certain drugs, the risk of accidental overdose (especially in children) outweighs environmental concerns. The FDA’s current flush list includes 15 specific medications, such as:- Fentanyl patches

- Oxycodone extended-release tablets

- Morphine sulfate extended-release

- Hydrocodone bitartrate and acetaminophen tablets

What NOT to Do

Avoid these dangerous myths:- Don’t flush everything. Only flush what’s on the FDA’s list.

- Don’t pour pills down the sink. That’s not safe disposal - it’s pollution.

- Don’t throw pills in the trash unaltered. Someone could find them.

- Don’t try to deactivate pills in their original bottle. That doesn’t work. You need the pouch or mixing method.

- Don’t keep them ‘just in case.’ If you don’t need them now, you won’t need them later. And the risk grows every day.

What If You’re in a Rural Area?

One in five Americans lives in a place with no take-back site within 50 miles. That’s over 14 million people. But you’re not out of options. In rural Wyoming, where distances are long, health departments started handing out deactivation pouches at clinics and pharmacies. They added simple visual instructions: a photo of the pouch, water, and trash can. Within a year, proper disposal rates jumped from 22% to 61%. If you’re in a medication desert:- Order Deterra or SUDS pouches online - many are shipped free with a prescription.

- Ask your pharmacist if they’ll mail you a pouch with your next refill.

- Keep a pouch in your car or bag so you’re ready when you get home.

Doctors and Pharmacists Should Be Helping - But Too Often, They Don’t

The American Society of Regional Anesthesia says every opioid prescription should come with disposal instructions. But a 2022 report found only 38% of prescribers actually talk about it. If your doctor didn’t mention disposal, ask. Say: “What should I do with these leftover pills?” It’s a simple question - but it saves lives. Pharmacists are trained to help. Walk into any major pharmacy and ask for the take-back bin or deactivation pouches. You don’t need a receipt. You don’t need to explain why. They’ve seen it all.

Real Stories, Real Impact

One mother in Ohio told her story on Reddit: “My 16-year-old found three oxycodone pills in my drawer after my knee surgery. I didn’t know they were still there. I didn’t know how to get rid of them. I felt sick. Now I keep a Deterra pouch in my bathroom. I use it every time I get a new prescription.” A nurse in Texas said her hospital started giving out pouches at discharge. Compliance jumped from 22% to 67%. “It’s not about trust,” she said. “It’s about making the right thing easy.”What’s Changing in 2025?

The opioid crisis isn’t slowing - but the response is getting smarter. - The DEA added 1,200 new collection sites in 2023, targeting Native American communities and rural counties. - The FDA is testing QR-code-enabled pouches that track usage anonymously to improve distribution. - By 2025, hospitals will be scored on how well they help patients dispose of opioids - part of a new national health survey. - States are using billions from opioid lawsuits to fund free disposal programs. California spent $5 million on kiosks. Wyoming gave out 10,000 pouches last year.Final Checklist: What to Do Today

If you have unused opioids, here’s your simple action plan:- Check the label. Is it on the FDA Flush List? If yes and you can’t get to a site, flush it.

- If not, find your nearest take-back site using the DEA’s website. Drop it off.

- If no site is nearby, buy a deactivation pouch from your pharmacy. Use it.

- If you can’t get a pouch, mix pills with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal in a container, and throw it away.

- Scrub your name off the empty bottle. Recycle it if your local program allows.

Can I throw unused opioids in the regular trash without mixing them?

No. Throwing pills in the trash without mixing them makes them easy to find and misuse. Always mix them with an unappetizing substance like coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt, then seal them in a container before tossing. This reduces the risk of someone digging them out.

What if I don’t know if my opioid is on the FDA flush list?

Check the medication label or ask your pharmacist. The FDA’s flush list includes only 15 specific opioids - mostly high-risk ones like fentanyl patches and extended-release oxycodone. If you’re unsure, don’t flush. Use a take-back program or deactivation pouch instead.

Are deactivation pouches really effective?

Yes. Lab tests show deactivation pouches like Deterra neutralize 99.9% of opioids within 30 minutes. They’re used in hospitals, clinics, and homes. They’re safer than flushing and more reliable than household disposal when done correctly.

Can I bring someone else’s unused opioids to a take-back site?

Yes. Take-back programs accept medications from anyone, even if they weren’t prescribed to you. You don’t need ID or proof of ownership. If you have unused pills from a family member, friend, or even a pet’s prescription, drop them off. It’s a public health service.

How often should I check my medicine cabinet for old opioids?

Check every 3 to 6 months. Opioids expire, but they don’t become safer over time. If you’ve had surgery, recovered from an injury, or stopped taking them for any reason, dispose of leftovers immediately. Don’t wait for a “good time.” The best time is right after you no longer need them.

Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness

Edward Hyde

December 2, 2025 AT 01:11Wow, another feel-good PSA from the nanny state. Next they’ll be forcing us to bury our aspirin in the backyard. People who steal pills are already criminals - this isn’t some public health crisis, it’s just lazy parenting and bad choices. I’ve got a bottle of oxycodone from 2018. I keep it. If my kid finds it, that’s their problem. Not mine.

Charlotte Collins

December 3, 2025 AT 07:32The statistics cited here are misleading. Diversion rates dropping by 82%? That’s not from longitudinal data - it’s from a single county study with a tiny sample size. And the 37% reduction in overdose deaths? Correlation isn’t causation. Communities with take-back programs also tend to have better mental health infrastructure, better policing, and higher income levels. This is a classic case of attributing complex social outcomes to a single intervention. The real solution is decriminalization and harm reduction - not more bins in Walgreens.

Margaret Stearns

December 4, 2025 AT 05:48I just used a Deterra pouch for the first time. It was so easy. I didn’t even know they existed until last week. I’ve been keeping my husband’s leftover pain meds since his surgery because I didn’t know what to do. Now I keep one in the bathroom. It’s like a little peace of mind. Thank you for explaining this so clearly.

Mary Ngo

December 5, 2025 AT 00:03Let us not ignore the deeper metaphysical implications of pharmaceutical control. The state’s insistence on regulating the disposal of opioids is not about safety - it is about the normalization of surveillance. Every pouch, every drop-off bin, every QR code embedded in these deactivation tools is a node in a network of behavioral tracking. We are being conditioned to surrender autonomy under the guise of public health. Who owns the data from these ‘anonymous’ tracking systems? Who profits? The pharmaceutical industry? The DEA? The same entities that flooded our communities with these drugs in the first place? This is not disposal. This is control.

Kenny Leow

December 6, 2025 AT 23:48As someone who grew up in rural Montana, I can tell you - take-back sites were a myth. We had one in the county seat, 80 miles away. My mom used coffee grounds and duct tape. It worked. I’m glad pouches are available now, but let’s not pretend this is new. People have been disposing of meds the hard way for decades. The real win here is making it easier. And yeah, I used a pouch last month. Smelled like a science experiment. But it felt right. 🙏

Kelly Essenpreis

December 7, 2025 AT 10:56Alexander Williams

December 8, 2025 AT 21:18The efficacy metrics presented lack methodological rigor. The 99.9% deactivation claim from pouch manufacturers is derived from in vitro assays under controlled conditions, not real-world environmental degradation scenarios. Furthermore, the term 'diversion' is operationally undefined - is it self-reported? Confirmed via forensic analysis? Without peer-reviewed, longitudinal, multi-site validation, these figures constitute anecdotal extrapolation masquerading as policy evidence. The FDA flush list remains the only empirically grounded protocol, and even that is subject to bioaccumulation concerns in aquatic ecosystems.

Suzanne Mollaneda Padin

December 10, 2025 AT 19:03I work in a hospital pharmacy. We started giving out Deterra pouches with every opioid script last year. Compliance went from 22% to 71%. People were shocked it was free. We didn’t even have to explain it - just handed them the pouch with the script. No judgment. No lecture. Just: 'Here, use this.' It’s not about guilt. It’s about removing friction. If you’re reading this and you’ve got old pills - just go to your pharmacy. Ask for the pouch. They’ll hand it to you like you’re buying aspirin. It’s that simple.

Lauryn Smith

December 12, 2025 AT 17:01I used to keep my mom’s leftover pain meds just in case she needed them again. Then I found out her neighbor’s grandson got into them and ended up in the ER. I felt awful. I didn’t know what to do. I found a take-back bin at the grocery store. I dropped them off. It took five minutes. I cried. Not because I was sad - because I finally did something right. If you’ve got old pills, don’t wait. Just go. It’s not a big deal. But it matters.

Bonnie Youn

December 14, 2025 AT 06:38Debbie Naquin

December 14, 2025 AT 09:52Disposal is a symptom, not a solution. The real question is why we are prescribing opioids in the first place - not how we dispose of them after. We have medicalized suffering. We have turned pain into a problem to be chemically erased. We have created a culture where discomfort is unacceptable. And now we are policing the residue of that ideology. The pill is not the enemy. The belief that pain must be eliminated at all costs is. Until we address that, we are rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Karandeep Singh

December 14, 2025 AT 19:02