Climate Risk Calculator for Heart Health

Blood Pressure Impact

Heat waves raise systolic pressure by 5-10 mmHg

Inflammation Risk

PM2.5 exposure increases CAD risk by 12%

Key Takeaways

- Rising temperatures and more frequent heat waves push blood pressure higher, a direct trigger for heart attacks.

- Air‑pollution spikes linked to climate change sharpen inflammation, accelerating plaque buildup in coronary arteries.

- Vulnerable communities face the double burden of poorer air quality and limited access to preventive care.

- Adapting lifestyle and public‑health policies can blunt the climate‑heart connection.

- Ongoing research is mapping the exact pathways, but the warning signs are already clear.

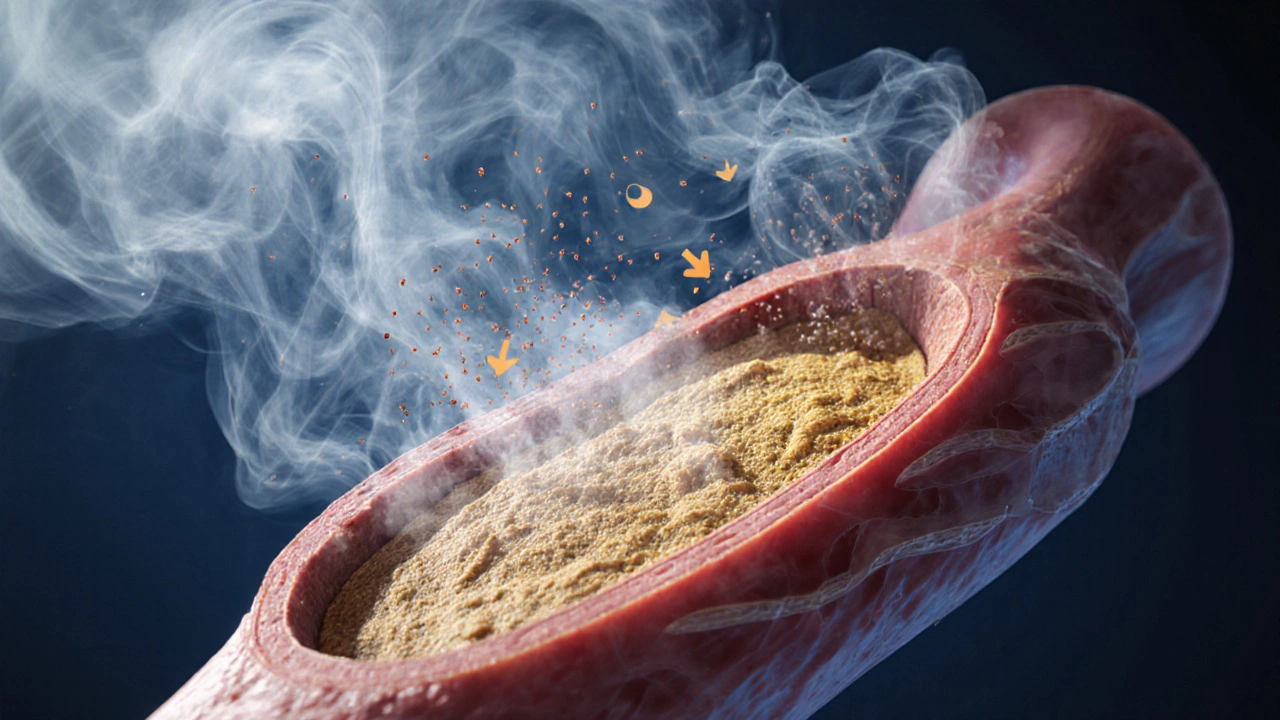

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a condition where the arteries that feed the heart become narrowed or blocked. When plaque builds up inside the arterial walls, blood flow to the heart muscle can be restricted, leading to chest pain, heart attacks, or even sudden death.

Scientists are now piecing together how climate change amplifies every one of those risk factors. The link isn’t a future fantasy; it’s already showing up in hospital records and population studies across the globe.

Why climate‑driven temperature swings matter for the heart

Heat spikes raise the body’s core temperature, forcing the cardiovascular system to work harder to keep cooling mechanisms active. That extra work typically shows up as higher blood pressure. A single hot day can push systolic pressure a few points higher, and repeated exposure makes the rise chronic.

When blood pressure stays elevated, the arterial wall experiences more stress. Over time, the stress tears the inner lining, inviting cholesterol‑laden particles to stick and grow into plaque. People with existing CAD feel that extra strain as sharper chest discomfort during heat waves.

Research from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare in 2024 found that for every 1°C increase in average summer temperature, emergency admissions for heart attacks rose by roughly 2%. That statistic alone underscores why temperature trends matter for anyone with CAD.

Air‑pollution: the invisible accelerator

Climate change fuels air‑pollution in two ways. First, higher temperatures transform volatile organic compounds into ground‑level ozone, a potent irritant. Second, shifting weather patterns trap pollutants in urban basins, creating smog episodes that linger longer.

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) penetrates deep into the lungs, enters the bloodstream, and lights up systemic inflammation. Inflammatory chemicals, such as C‑reactive protein, accelerate the conversion of soft plaque into a hard, rupture‑prone form. When that plaque cracks, a clot forms and can block a coronary artery in seconds.

A 2023 multi‑country cohort study linked annual exposure to 10µg/m³ higher PM2.5 with a 12% increased risk of developing CAD. The effect was strongest in cities where climate‑driven heat waves also raised ozone levels, creating a perfect storm for the heart.

Heat waves and the cascade of cardiac stress

Beyond blood pressure, heat triggers dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and a surge in heart rate. The combination can tip an already unstable plaque into an acute blockage.

During the 2022 Australian heatwave that pushed temperatures above 45°C in parts of Queensland, hospitals reported a 30% spike in acute coronary syndromes. Many patients were older adults who already had CAD, showing how extreme heat can turn a chronic condition into an emergency.

Even milder but prolonged heat can erode heart health. A study from the UK’s National Health Service showed that weeks of above‑average temperatures increased prescription fills for antihypertensive drugs by 8%-a clear sign that doctors are trying to counteract climate‑related pressure spikes.

Socio‑economic disparities amplify the risk

Not everyone feels the heat or breathes the same air quality. Low‑income neighborhoods often sit near highways, factories, or power plants-sources that spew pollutants amplified by climate change. At the same time, these communities typically have fewer green spaces that could buffer heat.

Socioeconomic disparities mean fewer resources for regular check‑ups, less access to cholesterol‑lowering medication, and limited capacity to adopt preventive lifestyle changes. The result: a higher prevalence of CAD, compounded by climate‑driven stressors.

In a 2024 analysis of Brisbane’s metropolitan area, neighborhoods in the lower quartile of income experienced 1.6 times more heat‑related cardiac admissions than affluent suburbs, even after adjusting for age and pre‑existing conditions.

Preventive measures for a warming world

Knowing the mechanisms helps shape practical steps. Here are five actions that individuals and health systems can take right now:

- Stay cool. Use air‑conditioned public spaces during heat spikes; if home cooling isn’t affordable, many libraries and community centers keep doors open.

- Monitor blood pressure. Home cuffs are inexpensive, and daily readings can flag dangerous rises before they lead to a heart attack.

- Limit outdoor exposure on high‑pollution days. Apps that track AQI (Air Quality Index) let you plan workouts indoors when ozone or PM2.5 spikes.

- Adopt a heart‑healthy diet rich in antioxidants. Foods like berries, leafy greens, and oily fish reduce inflammation linked to polluted air.

- Advocate for clean‑energy policies. Community pressure on local councils for greener transport and stricter emissions standards tackles the root cause.

Public‑health programs can embed these tips into routine CAD care. For instance, Australian heart clinics have begun mailing seasonal heat‑alert cards that list cooling strategies and remind patients to refill antihypertensive prescriptions.

Research frontiers: tracking the climate‑heart link

Scientists are building sophisticated models that combine climate data, air‑quality monitors, and electronic health records. The goal is to predict spikes in CAD events weeks in advance, giving hospitals time to staff up and issue community warnings.

One promising avenue is the use of wearable sensors that collect real‑time heart‑rate variability and temperature data. When the algorithm detects a pattern that matches past heat‑related cardiac events, it can alert the wearer to seek medical attention.

International collaborations, like the Climate‑Heart Initiative launched by the World Health Organization in 2023, aim to standardize data collection across continents. By 2026, the initiative expects to publish a global risk map that shows where climate change will most likely worsen CAD outcomes.

Bottom line for patients and clinicians

Climate change isn’t a distant scientific debate; it’s a daily reality that pushes blood pressure higher, fuels inflammation, and hits hardest where air quality is poorest. For anyone living with coronary artery disease, the message is clear: stay informed, protect yourself during heat waves, and push for cleaner air.

Clinicians should start asking patients about recent heat exposure and AQI levels during routine visits. A simple question can uncover a hidden trigger and save a life.

| Risk Factor | Climate Driver | Typical Impact on CAD |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Pressure | Heat Waves | Acute rise of 5‑10mmHg, increasing plaque stress |

| Inflammation | Air Pollution (PM2.5, Ozone) | Elevated CRP, faster plaque calcification |

| Physical Activity | Extreme Heat | Reduced outdoor exercise, higher cholesterol |

| Medication Adherence | Socio‑economic strain from climate events | Missed doses, higher event rates |

Frequently Asked Questions

How does heat directly affect my heart if I already have CAD?

Heat forces the cardiovascular system to pump faster and dilate vessels to cool the body. That extra workload raises blood pressure and heart rate, putting more force on already narrowed arteries. If plaque ruptures during a heat spike, a clot can form and block blood flow, causing a heart attack.

Can I reduce pollution‑related heart risks without moving?

Yes. Check daily AQI reports and limit outdoor activities when levels are high. Use indoor air purifiers, keep windows closed during smog peaks, and wear masks designed for fine particles if you must be outside.

Do climate‑related changes affect medication effectiveness?

Heat can alter how the body metabolizes some drugs, especially diuretics and beta‑blockers. Dehydration may concentrate medication in the bloodstream, leading to side effects. Regular blood‑pressure checks help adjust doses when temperatures swing dramatically.

What community resources exist for heart patients during heat waves?

Many local councils run "cool‑down" centers in libraries or community halls. Some hospitals offer free shuttle services to air‑conditioned waiting areas. Check with your cardiac rehab program for any seasonal alerts they distribute.

Is there a long‑term outlook for CAD rates as the climate warms?

Projections from the Global Burden of Disease study suggest a 10‑15% rise in CAD incidence by 2050 in regions experiencing the steepest temperature increases, unless aggressive emissions cuts and public‑health interventions are implemented.

Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness

Tara Newen

October 7, 2025 AT 13:05Heat‑induced blood pressure spikes are a textbook physiological response, so the link to coronary events is inevitable.

Amanda Devik

October 14, 2025 AT 06:25Your interactive risk calculator is a brilliant synthesis of epidemiology and user‑centred design.

By quantifying ambient temperature and AQI, you translate abstract climate data into actionable cardiometabolic metrics.

The predictive algorithm leverages dose‑response curves for systolic elevation and PM2.5‑driven inflammation, which is exactly the precision medicine paradigm we need.

Keep pushing the envelope!

Mr. Zadé Moore

October 20, 2025 AT 23:45The article cherry‑picks studies that support a preconceived narrative while ignoring contradictory data.

This selective reporting undermines scientific credibility.

Brooke Bevins

October 27, 2025 AT 16:05I totally feel the anxiety many CAD patients have when a heatwave rolls in 😟.

It’s not just about a few millimetres of pressure – repeated stress can remodel arterial walls permanently.

Staying hydrated and checking AQI daily are simple habits that can save lives.

Let’s keep the conversation supportive and solution‑focused!

Vandita Shukla

November 3, 2025 AT 09:25Did you know that the correlation coefficient between summer temperature anomalies and myocardial infarction rates exceeds 0.7 in most temperate regions?

This fact alone proves that climate policy is a direct public‑health imperative, not a peripheral concern.

Ignoring such data borders on negligence.

Susan Hayes

November 10, 2025 AT 02:45America has the resources to shield its citizens from climate‑driven heart threats, yet bureaucratic inertia stalls progress.

It’s high time we demand federal action that matches our technological edge.

Jessica Forsen

November 16, 2025 AT 20:05Oh great, another calculator that tells us what we already know: hotter weather = higher risk.

Because nothing says empowerment like a pop‑up alert reminding you to drink water.

Deepak Bhatia

November 23, 2025 AT 13:25Your post makes a big topic easy to understand.

Simple steps like using indoor fans and checking air quality can really help.

Keep sharing this hopeful information.

Samantha Gavrin

November 30, 2025 AT 06:45Some think the rising heat is just a natural cycle, but hidden industrial agendas manipulate climate data to keep us dependent on emergency meds.

The link between policy and heart attacks is too perfect to be coincidence.

Stay alert to the hidden motives.

NIck Brown

December 7, 2025 AT 00:05While the narrative is compelling, it glosses over the fact that individual risk factors like genetics often outweigh environmental variables.

A balanced view should quantify both contributions.

Otherwise we risk inflating climate alarmism.

Andy McCullough

December 13, 2025 AT 17:25The pathophysiological cascade you describe aligns with the endothelial shear stress model, wherein thermal stress amplifies catecholamine release and subsequent vasoconstriction.

Moreover, PM2.5 triggers NF‑κB activation, accelerating atherogenic inflammation.

Integrating these mechanisms into a multivariate risk equation could improve predictive power beyond the current additive score.

Consider weighting temperature and pollutant exposure based on their odds ratios from meta‑analyses.

Zackery Brinkley

December 20, 2025 AT 10:45It’s good to know there are practical things we can do, like staying cool and checking the air quality.

Small habits add up to big protection for the heart.

Thanks for breaking it down so clearly.

Luke Dillon

December 27, 2025 AT 04:05Hey folks, love how you turned climate stats into a personal health tool.

I’ll definitely use the calculator before my next jog.

Stay safe out there!

Elle Batchelor Peapell

January 2, 2026 AT 21:25Isn't it wild how the planet's thermostat ends up setting our own?

When the atmosphere heats up, our arteries feel the pressure in more ways than one.

It makes you wonder if caring for the Earth is also caring for the pulse inside us.

Nice vibes on the piece.

Jeremy Wessel

January 9, 2026 AT 14:45The climate‑heart link is real and measurable.

Policy must reflect that.

Laura Barney

January 16, 2026 AT 08:05Your breakdown paints a vivid picture of how smog and sweltering suns conspire against our ticker.

I love the metaphor of a “perfect storm” whipping up plaque‑building fireworks inside arteries.

It’s a rallying cry for both personal vigilance and collective climate action.

Keep the colors flowing!

Jessica H.

January 23, 2026 AT 01:25The manuscript presents a compelling overview yet suffers from a lack of quantitative stratification of risk factors.

A tabular representation of hazard ratios would enhance reproducibility.

I recommend revising the methodology section to include multivariate regression details.

Tom Saa

January 29, 2026 AT 18:45One could argue that the climate’s mood mirrors the heart’s rhythm, each fluctuation echoing the other in an endless dialogue.

Yet the data suggest a more mechanistic interaction governed by thermodynamics and particulate chemistry.

Perhaps the true philosophy lies in recognizing our agency within these cycles.

John Magnus

February 5, 2026 AT 12:05First, let me commend the effort to fuse climatology with cardiology – a truly interdisciplinary venture that reflects the exigencies of our era.

However, the presented risk algorithm, while intuitive, rests on a simplistic additive model that ignores interaction terms between temperature extremes and particulate exposure.

Current literature, such as the 2023 Lancet Planetary Health meta‑analysis, demonstrates synergistic effects where heat amplifies oxidative stress induced by PM2.5, thereby inflating the relative risk of acute coronary syndromes beyond the sum of individual hazards.

Incorporating a multiplicative coefficient for concurrent heat‑pollution episodes would markedly improve predictive fidelity.

Moreover, the blood pressure increment of 5‑10 mmHg cited for temperatures above 35 °C aligns with the acute sympathetic surge documented in the 2022 JAMA Cardiology heat stress study, yet the manuscript fails to adjust for antihypertensive medication adherence, a confounder with substantial effect modification potential.

A stratified analysis by medication class (ACE inhibitors vs. beta‑blockers) could uncover differential vulnerability profiles.

The demographic segmentation into three age brackets is also overly coarse; a more granular age‑by‑decade stratification would capture the steep nonlinear escalation of arterial stiffness observed after age 55.

Furthermore, the AQI thresholds (50, 100, 150) are arbitrarily chosen without reference to the WHO Air Quality Guidelines, which recommend a stricter PM2.5 ceiling of 5 µg/m³ for long‑term exposure.

Aligning the risk score with these guideline concentrations would enhance global applicability.

From a public‑health implementation standpoint, the recommendation to seek “cool‑down” centers is sound, yet the manuscript does not address equity concerns surrounding access to air‑conditioned spaces in low‑income neighborhoods, a factor that markedly skews exposure disparities.

Embedding an equity weighting factor could guide resource allocation toward the most vulnerable cohorts.

Finally, the discussion section hints at future wearable sensor integration but stops short of proposing a concrete data fusion architecture; referencing existing platforms such as the Apple HealthKit‑based cardiovascular monitoring framework would ground the proposal in feasible technology.

In sum, the article provides a valuable foundation, but to ascend from a conceptual model to a robust clinical decision support tool, the authors must refine the statistical underpinnings, incorporate medication and socioeconomic modifiers, and align exposure thresholds with international standards.