What is compulsory licensing, really?

Compulsory licensing isn’t about stealing patents. It’s about saying: when lives are at stake, patents can’t be a barrier. Imagine a life-saving cancer drug priced at $10,000 a year - and no one can make a cheaper version because the patent is locked down. A government steps in, allows a local company to produce the same medicine for $500, and pays the original maker a fair fee. That’s compulsory licensing. It’s a legal tool written into international law, not a loophole. And it’s been used, repeatedly, when the world needed it most.

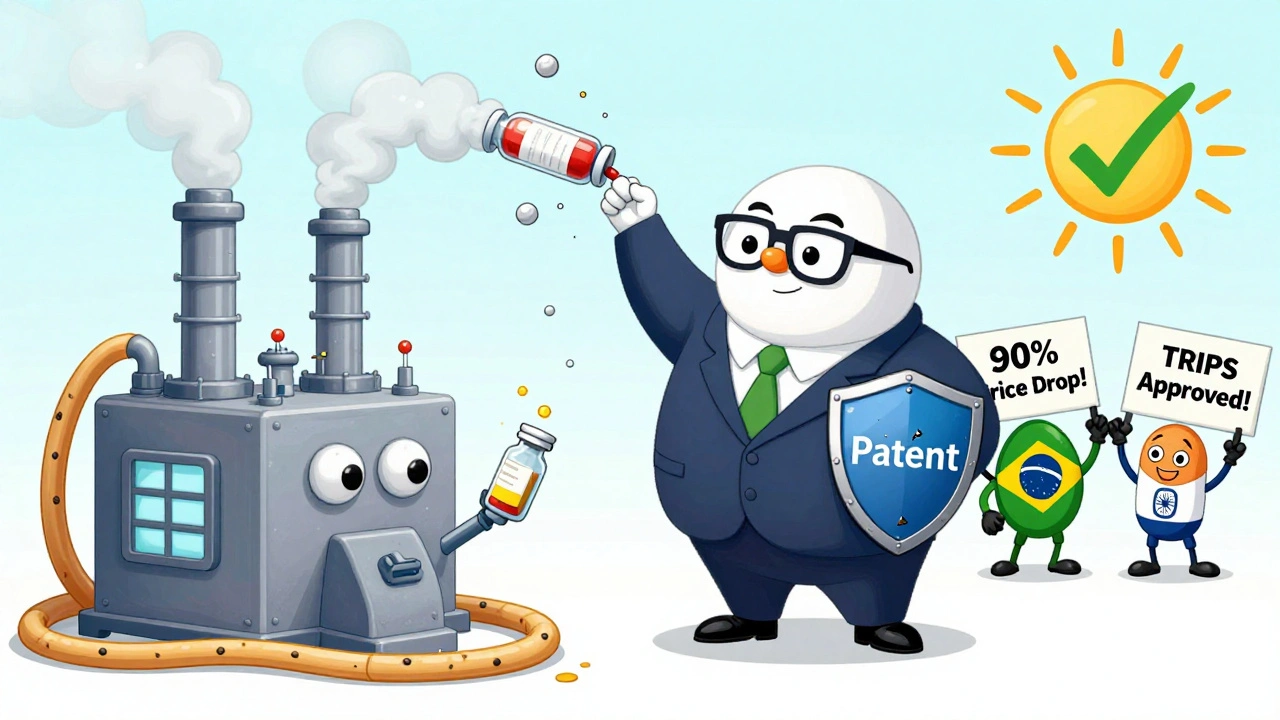

How did this even become legal?

The idea isn’t new. Back in 1883, countries agreed in the Paris Convention that if a patent wasn’t being used locally, others could step in. But the real foundation came in 1994 with the TRIPS Agreement under the World Trade Organization. Article 31 of TRIPS made it official: governments can authorize third parties to use a patented invention without the owner’s permission - as long as they pay fair compensation. This wasn’t a radical move. It was a safety valve. The world recognized that patents exist to encourage innovation, not to block access when people are dying.

When does it actually get used?

Most of the time, it’s for medicines. Between 2000 and 2020, 95% of all compulsory licenses reported to the WTO were for drugs. Not for smartphones. Not for software. For cancer treatments, HIV meds, and vaccines. During the COVID-19 pandemic, over 40 countries - including Germany, Canada, and Israel - prepared to issue compulsory licenses for coronavirus treatments and vaccines. In 2006, Thailand issued licenses for HIV and heart drugs, slashing prices by up to 90%. Brazil did the same with HIV drugs, cutting the cost of efavirenz from $1.55 per tablet to $0.48. These aren’t hypotheticals. These are real people getting treatment because the system allowed it.

How does it work in the U.S.?

The U.S. has the rules, but rarely uses them. There are three main paths: Title 28, U.S.C. § 1498 lets the federal government use any patented invention - like a military tech or a vaccine - and pay compensation later through the Court of Federal Claims. The Bayh-Dole Act lets the government step in if a federally funded invention isn’t being made available to the public. And the Clean Air Act allows compulsory licensing for environmental tech. But here’s the catch: since 1945, only 10 compulsory licenses have been issued under these laws - all for government use. No drug company has ever had its HIV or cancer drug forcibly licensed in the U.S. Why? Because the system is designed to be slow, expensive, and politically risky. The threat of a license often works better than the license itself.

India and Brazil: Where it actually works

India has issued 22 compulsory licenses since 2005 - more than any other country. The first was for Nexavar, a liver cancer drug made by Bayer. The price dropped from $5,500 a month to $175. The company sued. It took eight years. India won. Brazil issued three licenses for HIV drugs, forcing price cuts that saved thousands of lives. These countries didn’t just have the law - they had the political will. They didn’t wait for negotiations to drag on. They acted when people were dying. And they didn’t break the rules. They used them exactly as TRIPS intended.

What’s the catch? Is it bad for innovation?

Pharma companies say yes. They claim compulsory licensing scares off investment. A 2018 study found a 15-20% drop in R&D spending in countries that use it often. The IFPMA says each license announcement causes an 8.2% stock drop for the affected company. But here’s the other side: Dr. Brook Baker found that the mere threat of a compulsory license led to voluntary price cuts on 90% of HIV drugs in poor countries since 2000. Companies lowered prices to avoid the license. That’s not innovation killing - that’s market pressure working. And let’s not forget: most drugs are built on publicly funded science. The NIH and other government labs paid for the early research. The patent system is supposed to reward commercialization - not lock away public knowledge forever.

Why don’t more countries use it?

Because it’s hard. Even if the law says you can do it, you need lawyers, patent experts, manufacturing capacity, and political courage. The WHO says 60% of low- and middle-income countries lack the technical ability to issue a license properly. Some countries don’t even have the legal framework written clearly. Others are scared of trade retaliation - the U.S. has listed countries that use compulsory licensing on its “priority watch list.” But no sanctions have been applied since 2012. And the world is changing. In 2022, the WTO agreed to a temporary waiver for COVID-19 vaccines - the biggest shift in patent rules in decades. It lets poor countries produce vaccines without permission until 2027. Only 12 factories in 8 countries have used it so far - but the door is open.

What’s next?

The WHO is drafting a Pandemic Treaty that would make compulsory licensing automatic during global health emergencies. The EU is pushing for rules that force patent holders to offer licenses within 30 days - or lose control. Experts predict a 40% rise in compulsory licenses by 2028, driven by antimicrobial resistance and climate-related health tech. The future isn’t about abolishing patents. It’s about balancing them. Patents should protect innovation - not prevent access. And when a pandemic hits, or a child can’t afford insulin, the law already gives governments the power to act. The question isn’t whether they can. It’s whether they will.

Can a company stop a compulsory license?

Yes - but only if they can prove they’re already doing enough. In India, Bayer fought the Nexavar license for eight years. They claimed they were making the drug available, even though only a few hundred patients could afford it. The court said: selling a drug at $5,500 a month isn’t “reasonable availability.” The law doesn’t require a company to sell at cost. But it does require them to make it accessible. If they don’t, the government can step in. Courts around the world have consistently ruled that public health trumps profit when lives are on the line.

Does compulsory licensing mean the patent is gone?

No. The patent holder still owns it. They just don’t get to control who makes it or at what price. The government grants a license to someone else - usually a generic manufacturer - to produce the drug. The original company still gets paid. In India, it’s 6% of net sales. In the U.S., courts use 15 factors to calculate a fair royalty. The patent isn’t canceled. It’s shared. And that’s the point: innovation should serve people, not just shareholders.

Can I use this if I’m a small company?

Not directly. Compulsory licenses are almost always issued to government-backed manufacturers - not private firms. But if you’re a generic drugmaker, you can apply to your government to request a license. You’ll need to show you can produce the drug, that the patent holder refused a voluntary deal, and that there’s a public need. It’s a long process. Most applications take 18-24 months. Only 22% of licenses are initiated by private companies. The real power lies with governments.

What’s the difference between compulsory licensing and parallel importing?

Parallel importing means buying a drug from a country where it’s sold cheaper and bringing it in. Compulsory licensing means making it yourself. One is about price arbitrage. The other is about production rights. Both reduce prices. But only compulsory licensing lets a country build its own supply chain - which matters when global shortages hit.

Is this legal under international law?

Yes. TRIPS explicitly allows it. The Doha Declaration in 2001 confirmed that countries have the right to prioritize public health over patents. No country has ever been legally punished for using compulsory licensing. The U.S. may complain on paper - but it uses the same tool for its own military tech. The rules are clear. The politics are messy. But the law is on the side of public health.

Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness

Sarah Clifford

December 11, 2025 AT 04:00Regan Mears

December 11, 2025 AT 13:56Doris Lee

December 12, 2025 AT 01:13Michaux Hyatt

December 12, 2025 AT 08:19Queenie Chan

December 13, 2025 AT 22:59Raj Rsvpraj

December 15, 2025 AT 02:26Jack Appleby

December 16, 2025 AT 15:03Rebecca Dong

December 17, 2025 AT 11:25