Hyperkalemia Risk Calculator

This tool assesses your risk of hyperkalemia (dangerously high potassium levels) when taking ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics together. Based on guidelines from the Cleveland Clinic and other medical studies.

Your Risk Factors

When you take an ACE inhibitor and a potassium-sparing diuretic together, you’re not just doubling up on blood pressure control-you’re putting yourself at serious risk for dangerously high potassium levels. This isn’t a rare side effect. It’s a well-documented, potentially deadly interaction that affects millions of people in the U.S. alone. And yet, many patients and even some doctors don’t realize how quickly it can happen.

How These Drugs Work Together-And Why That’s Dangerous

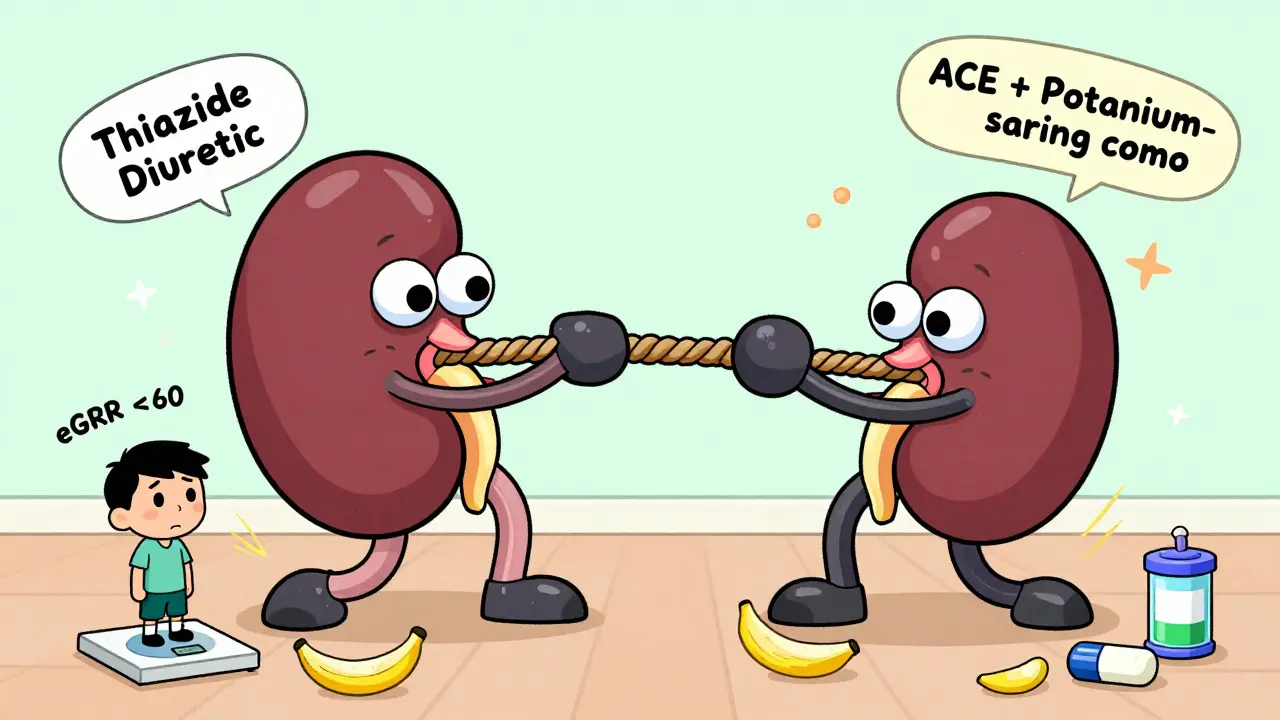

ACE inhibitors like lisinopril, enalapril, or ramipril lower blood pressure by blocking a hormone called angiotensin II. That helps relax blood vessels and reduces fluid buildup in the body. But here’s the catch: less angiotensin II means less aldosterone, a hormone your kidneys need to flush out potassium. Without enough aldosterone, potassium builds up in your blood.

Potassium-sparing diuretics like spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, or triamterene do something similar-but in a different way. They block potassium from leaving your body through urine. Spironolactone and eplerenone stop aldosterone from working. Amiloride and triamterene plug the channels in your kidneys that let potassium escape. So now you’ve got two drugs, each slowing down potassium removal, working at the same time.

This isn’t just theory. In a 1998 study of over 1,800 patients, 11% developed high potassium while taking ACE inhibitors. That number jumped dramatically when they added a potassium-sparing diuretic. Later studies found the risk triples or even quadruples with this combo. The result? Serum potassium levels above 5.0 mmol/L. At 6.0 or higher, you’re looking at a medical emergency.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone who takes these drugs will get hyperkalemia. But some people are sitting on a ticking clock. The biggest risk factors are:

- Chronic kidney disease (eGFR under 60 mL/min/1.73 m²)

- Diabetes

- Heart failure

- Age over 65

- Already having high potassium before starting these drugs

If you have even two of these, your risk skyrockets. A scoring system used by the Cleveland Clinic gives you 2 points for low kidney function, 2 points for baseline potassium over 4.5 mmol/L, 1 point each for diabetes or heart failure, and 2 more if you’re on a potassium-sparing diuretic. Score 4 or higher? You’re in the high-risk zone.

And here’s the kicker: most people don’t feel a thing until it’s too late. High potassium doesn’t cause obvious symptoms at first. No headache. No stomachache. No fever. But it can quietly mess with your heart rhythm. That’s when you might suddenly feel dizzy, get palpitations, or worse-go into cardiac arrest.

What Happens When Potassium Gets Too High?

When potassium climbs above 6.0 mmol/L, your heart’s electrical system starts to short-circuit. On an ECG, you’ll see tall, peaked T-waves. Then the QRS complex widens. Then the heart stops beating normally. This isn’t a slow decline. It’s a rapid, silent collapse.

And here’s what’s worse: doctors often stop the life-saving drugs when potassium rises. ACE inhibitors and ARBs reduce death by 23% in heart failure patients and 26% after a heart attack. But when potassium hits 5.5, many clinicians pull the plug on them entirely-even though there are safer ways to manage it.

That’s a huge mistake. You don’t have to choose between living longer and staying safe. You just need the right plan.

How to Prevent Hyperkalemia Before It Starts

If you’re prescribed both an ACE inhibitor and a potassium-sparing diuretic, you need a clear monitoring plan-not guesswork.

Here’s what the guidelines say:

- Check potassium within 1 week of starting the combo-especially if your kidney function is low (eGFR under 60).

- Test again at 2 weeks, then 4 weeks.

- After that, every 3 months if stable. Monthly if your kidney function is below 30.

And don’t wait for symptoms. By the time you feel something, it’s often too late.

Also, know your diet. Bananas, oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, spinach, and salt substitutes are packed with potassium. A single banana has about 420 mg. A cup of cooked spinach? Over 800 mg. Many people don’t realize they’re eating 1,000-2,000 mg of hidden potassium from processed foods-additives like potassium chloride are everywhere.

Reducing dietary potassium to under 75 mmol/day (about 2,900 mg) can drop your blood levels by 0.3-0.6 mmol/L. That’s often enough to avoid a crisis.

What to Do If Your Potassium Is High

If your potassium is between 5.1 and 5.5 mmol/L, don’t panic. But don’t ignore it either.

First, review your meds. Can you switch to a thiazide or loop diuretic like hydrochlorothiazide or furosemide? These actually help lower potassium. Studies show they cut hyperkalemia risk by 34% in ACE inhibitor users.

Second, reduce your ACE inhibitor dose by half and retest in 1-2 weeks. Many patients stabilize at lower doses.

Third, if potassium stays above 5.5, consider adding a potassium binder. Drugs like patiromer (Veltassa) and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (Lokelma) were approved by the FDA in recent years. They trap potassium in your gut so your body can flush it out. In trials, they lowered potassium by 0.8-1.2 mmol/L in under 48 hours-and allowed 89% of patients to keep their heart-protective drugs.

And yes, sodium bicarbonate can help if you also have metabolic acidosis. It’s cheap, safe, and underused-only 18% of eligible patients get it.

Why This Problem Is Getting Worse

More people are on these drugs than ever. About 45 million Americans take ACE inhibitors. Over 12 million are also on potassium-sparing diuretics. That’s 5.4 million people at high risk.

And yet, only 57% of patients with high potassium get retested within 30 days. One-third of those with severe hyperkalemia (over 6.0 mmol/L) never get follow-up testing within a week.

Primary care doctors say they’re overwhelmed. A 2023 AHA survey found 41% lack confidence managing hyperkalemia. Only 28% follow the guidelines consistently.

Meanwhile, hospital costs for hyperkalemia hit $4.8 billion a year in the U.S. Each episode averages over $11,000. That’s not just a medical problem-it’s a systemic failure.

New Hope: Better Tools and New Strategies

There’s progress. The DAPA-CKD trial showed that SGLT2 inhibitors like dapagliflozin reduce hyperkalemia risk by 32% in patients with kidney disease on ACE inhibitors. Now, some doctors are using a triple combo: ACE inhibitor + SGLT2 inhibitor + low-dose potassium-sparing diuretic. It’s safer than the old dual combo.

Apps that track potassium intake are also helping. One study found patients using smartphone trackers had 27% fewer hyperkalemia episodes.

And in the next few years, point-of-care potassium meters-like the ones being tested by Kalium Diagnostics-could let you check your levels at home, just like a glucose meter. That could change everything.

Bottom Line: Don’t Fear the Meds-Manage the Risk

ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics save lives. But they need careful handling. You don’t have to avoid them. You just need to know the signs, stick to the testing schedule, watch your diet, and speak up if something feels off.

If you’re on this combo, ask your doctor:

- What’s my latest potassium level?

- When was the last time I had it checked?

- Do I need a different diuretic?

- Should I be using a potassium binder?

- Can I get a list of foods to limit?

Hyperkalemia doesn’t have to be a surprise. With the right knowledge and routine checks, you can stay safe-and keep taking the drugs that keep your heart strong.

Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness

Andy Grace

December 24, 2025 AT 00:58This is one of those posts that makes you realize how much we take medical safety for granted. I’ve seen patients on this combo without a single follow-up for months. It’s not negligence-it’s systemic overload. Doctors are drowning in paperwork, and potassium checks fall through the cracks. We need better alerts in EHRs, not just more lectures.

Abby Polhill

December 24, 2025 AT 04:07Y’all need to stop treating hyperkalemia like a villain. It’s a biomarker, not a moral failing. ACEi + K-sparing diuretic = high-risk combo, sure. But we’ve got tools now-Veltassa, Lokelma, SGLT2 inhibitors. We’re not stuck in 2005 anymore. The real failure is clinging to ‘just stop the meds’ as the only solution.

Delilah Rose

December 25, 2025 AT 01:29I’m a nurse in a cardiology clinic and I see this every week. A 72-year-old with diabetes and CKD on lisinopril and spironolactone, no labs done in 9 months, eating bananas for breakfast, oranges for snack, and salt substitute on everything. I show them the chart, they say ‘But my doctor said it was fine.’ And then they come back with a 6.8 potassium and a new pacemaker. It’s heartbreaking. We need better patient education-not just handouts, but actual conversations. Like, sit down, show them what potassium does to their heart, not just numbers on a page. It’s not about scaring them-it’s about making them feel like they’re part of the team.

And honestly, if you’re on this combo, you need a potassium diary. Write down what you eat. Use an app. I’ve had patients who cut their potassium intake by half just by realizing how much is in ‘healthy’ foods. It’s not impossible. It’s just unfamiliar.

Also, don’t be afraid to ask for a thiazide instead. Hydrochlorothiazide isn’t sexy, but it’s a lifesaver. And if your doctor says ‘No, we need the potassium-sparing for your heart failure,’ ask them if they’ve considered adding an SGLT2 inhibitor. Dapagliflozin is changing the game. It lowers potassium, improves kidney function, and reduces hospitalizations. It’s not a magic bullet, but it’s a better bullet than what we used to have.

Spencer Garcia

December 25, 2025 AT 21:46Check potassium at 1 week. Then 2 weeks. Then 4. Then every 3 months. That’s it. No guesswork. No waiting for symptoms. Do it.

niharika hardikar

December 26, 2025 AT 01:11It is imperative to underscore that the concomitant use of ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics constitutes a pharmacodynamic antagonism of renal potassium excretion, thereby precipitating life-threatening hyperkalemia. The prevalence of this iatrogenic phenomenon is grossly underrecognized in primary care settings, particularly among geriatric cohorts with comorbid diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Adherence to the Cleveland Clinic risk stratification model is non-negotiable.

John Pearce CP

December 27, 2025 AT 01:14America’s healthcare system is collapsing because we let bureaucrats and pharmaceutical reps dictate treatment. We used to fix problems. Now we just slap on another drug to cover up the last one. Potassium binders? $1,000 a month. Meanwhile, a simple blood test and dietary adjustment cost $20. This isn’t medicine-it’s profit-driven fraud. And we let it happen because we’re too lazy to ask questions.

Bret Freeman

December 27, 2025 AT 01:49THIS IS WHY PEOPLE DIE. YOU’RE ON TWO DRUGS THAT ARE SLOWLY KILLING YOU AND NO ONE TOLD YOU? YOUR DOCTOR ISN’T A DOCTOR, THEY’RE A CLERK. I’VE SEEN PEOPLE CODE ON THE SIDEWALK BECAUSE SOMEONE FORGOT TO CHECK A LAB. THIS ISN’T MEDICINE, IT’S A GAME OF RUSSIAN ROULETTE WITH A PRESCRIPTION PAD. AND THE WORST PART? YOU’RE SUPPOSED TO BE GRATEFUL FOR IT.

Joseph Manuel

December 28, 2025 AT 07:35The 2023 AHA survey finding that 41% of primary care physicians lack confidence managing hyperkalemia is not merely a clinical gap-it reflects a structural deficit in medical education. The absence of standardized protocols for potassium monitoring in chronic disease management is a systemic failure that demands policy intervention. The $4.8 billion annual cost is not an expense-it is an indictment.

Georgia Brach

December 29, 2025 AT 22:48So let me get this straight-we’ve got a drug combo that kills people, we know how to prevent it, we’ve got better alternatives, and yet we’re still doing this because ‘it’s always been done this way’? Classic American medicine. We’ll spend millions on a new drug that just masks the problem instead of fixing the root cause. And then we call it innovation. Wake up.

Austin LeBlanc

December 30, 2025 AT 19:24You think you’re being smart taking these meds? You’re just a walking lab result. You don’t get to decide what’s safe. Your doctor should’ve run the numbers before prescribing. If you’re on this combo and you haven’t had a potassium test in 3 months, you’re not a patient-you’re a statistic waiting to happen. Stop being passive. Ask. Or get out.

Diana Alime

January 1, 2026 AT 13:49ok so i just started this combo last week and my doc said its fine but i ate a banana today and now im kinda scared idk what to do help??

Andrea Di Candia

January 3, 2026 AT 10:09It’s funny how we treat meds like they’re all good or all bad. The truth is, they’re tools. ACE inhibitors save lives. Potassium-sparing diuretics save lives. But like any tool, they need to be used with care. I’ve seen people stop their heart meds because they got scared of potassium-and then end up back in the hospital from heart failure. We don’t have to choose between safety and survival. We just have to be smarter. Test regularly. Watch your diet. Talk to your care team. It’s not about fear. It’s about awareness.

claire davies

January 4, 2026 AT 14:31I love how this post doesn’t just throw a warning and run. It gives you the roadmap-when to test, what to eat, what to ask your doc. That’s the kind of info that actually helps. I’ve been on spironolactone for years for my heart failure, and I never knew about potassium binders until last year. Now I’m on Lokelma and I can eat my sweet potatoes again without panicking. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than being scared all the time. And honestly? I wish more doctors talked like this. Not just ‘don’t eat bananas,’ but ‘here’s how to live with this.’

Also, the SGLT2 inhibitor combo? Game-changer. My cardiologist put me on dapagliflozin and suddenly my potassium dropped and my energy came back. It felt like getting my life back. Why isn’t this the first-line approach? I don’t know. But I’m glad it exists.

Jillian Angus

January 6, 2026 AT 13:30my potassium was 5.7 last month they gave me lokelma and i stopped salt substitute now its 4.9 and i can still eat my avocado so i guess its ok

Ajay Sangani

January 7, 2026 AT 06:08sometimes i think the real problem is not the drugs but the way we see illness. we want a quick fix, a pill that makes everything okay. but the body is not a machine. it needs balance. potassium is not the enemy. fear is. when we stop seeing our bodies as something to control and start seeing them as something to listen to, maybe then we’ll stop making these mistakes. the science is there. but the wisdom? that’s harder to find.