Abrasion is a superficial skin injury where the outer layers are rubbed or scraped off, typically caused by a fall, a bike accident, or a rough surface. While it sounds simple, the body’s response unfolds in a tightly coordinated series of events that most people overlook. Knowing what to expect can keep you from panicking, reduce the risk of infection, and help the wound close faster.

What Exactly Is an Abrasion?

In plain terms, an abrasion strips away the Skin the body’s largest organ, composed of multiple layers that protect internal tissues. The most damaged part is the Epidermis the thin, outermost skin layer packed with keratinocytes, which normally acts as a barrier against microbes and fluid loss. When the epidermis is scraped away, the underlying Dermis a tougher layer rich in collagen, blood vessels, and nerves may be exposed, triggering pain, bleeding, and the classic inflammatory response.

The Body’s Healing Stages

Wound healing follows three overlapping phases: inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. Each phase has its own timeline, cellular players, and goals.

1. Inflammatory Phase (0‑4 days)

Almost immediately after the skin is breached, blood vessels constrict to limit bleeding. Then they dilate, allowing white blood cells to rush in. This rush is called Inflammation a protective reaction that brings immune cells, heat, and swelling to the wound site. The main job is to clear debris and any invading microbes.

Typical signs: redness, warmth, slight swelling, and a throbbing ache. If the redness spreads beyond the wound edges, you might be dealing with an Infection the uncontrolled growth of bacteria or fungi in the wound tissue, which requires prompt medical attention.

2. Proliferative Phase (4‑14 days)

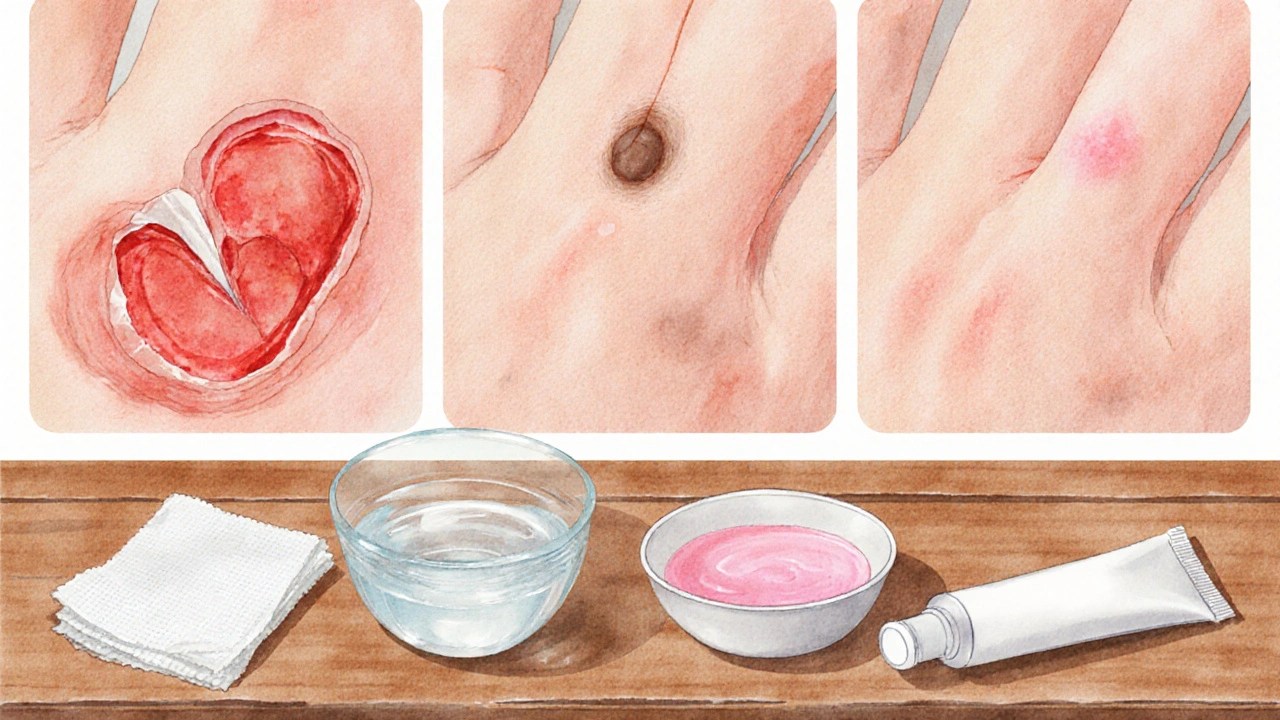

Once the area is clean, the body shifts gears. New tissue called Granulation tissue a pink, spongy matrix rich in new blood vessels and collagen fibers starts to fill the defect. Simultaneously, skin cells at the wound edge begin to slide forward in a process known as Re‑epithelialization the migration and proliferation of keratinocytes to close the wound surface. This is why you’ll often see a thin pink film forming over a few days.

During this window, keeping the wound moist (but not soggy) dramatically speeds up cell migration. Too much dryness forms a scab that actually slows down healing by creating a physical barrier.

3. Remodeling Phase (2 weeks‑1 year)

Even after the surface looks sealed, the deeper layers keep strengthening. Collagen fibers re‑align, and the scar tissue becomes less noticeable. This phase can last months, which explains why a scar might still be reddish or raised weeks after the injury.

Factors such as age, nutrition, and genetics dictate how smooth the final scar will be. Younger people generally remodel faster because their fibroblasts are more active.

Typical Healing Timeline for Common Abrasions

Below is a quick reference for what most people experience. Individual timelines can vary, but these benchmarks help set realistic expectations.

- Minor scrape (e.g., a knee nick from a fall): Redness and pain subside within 2‑3 days; surface closes by day 5‑7; full remodeling by 4‑6 weeks.

- Moderate abrasion (e.g., a bike‑handlebar scrape): Noticeable inflammation for 3‑5 days; granulation tissue evident by day 7‑10; complete closure by 2‑3 weeks; remodeling up to 3‑4 months.

- Severe abrasion (large area or deep to dermis): Prolonged inflammation (up to 7 days); possible need for medical dressing; full closure may take 4‑6 weeks; remodeling can extend beyond 6 months.

Step‑by‑Step At‑Home Care

- Wash Your Hands. Clean hands with soap and water before touching the wound to avoid introducing new germs.

- Gentle Rinse. Use cool, running water or sterile saline to flush out dirt and debris. Avoid harsh scrubbing; a soft stream is enough.

- Disinfect (if needed). Apply a mild Antiseptic a chemical agent that reduces bacterial load, such as povidone‑iodine or chlorhexidine only if the wound is visibly dirty. Over‑use can delay healing.

- Apply a Protective Layer. Thinly spread a petroleum‑based ointment or a zinc‑oxide cream to keep the area moist. This creates a barrier against air‑borne microbes.

- Cover Appropriately. Use a non‑adhesive sterile gauze pad held with a breathable adhesive bandage. Change the dressing daily or when it becomes wet.

- Monitor for Infection. Look for increasing redness, swelling, pus, or a foul odor. If any appear, seek professional care.

- Support Healing From Inside. Stay hydrated, eat protein‑rich foods, and consider vitamin C or zinc supplements to aid collagen synthesis.

Comparing Common Treatment Options

| Option | Cost (AU$) | Effectiveness | Infection Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plain Water Rinse | 0 | Good for debris removal | Low |

| Saline Solution | 5‑10 (pre‑made) | Excellent for gentle cleaning | Very Low |

| Antiseptic (povidone‑iodine) | 8‑12 per bottle | High for bacterial reduction | Moderate (can irritate) |

| Topical Antibiotic Ointment | 6‑15 per tube | Very High for preventing infection | Low (watch for allergy) |

| Hydrocolloid Dressing | 3‑7 per patch | Excellent moisture control | Low |

For most everyday scrapes, a simple saline rinse followed by a thin layer of petroleum jelly and a breathable bandage is enough. Reserve antiseptics and antibiotic ointments for deeper or contaminated wounds.

Factors That Can Speed Up or Slow Down Healing

Understanding what influences the process helps you make smarter choices.

- Age. Older skin produces less collagen, extending the remodeling phase.

- Nutrition. Protein, vitamin C, and zinc are essential for new tissue formation.

- Smoking. Nicotine narrows blood vessels, limiting oxygen delivery to the wound.

- Underlying health conditions. Diabetes, peripheral artery disease, or immune disorders can impair all three healing phases.

- Moisture level. Too dry forms hard scabs; too wet encourages maceration and bacterial growth.

When to Seek Professional Medical Help

Most abrasions heal at home, but certain red flags demand a doctor’s attention:

- Rapidly spreading redness or swelling beyond the wound margins.

- Visible pus, foul odor, or increasing pain after 48 hours.

- Deep abrasion exposing muscle, tendon, or bone.

- Wound larger than a postage stamp (about 2cm) that won’t stop bleeding after applying pressure for 10 minutes.

- Any abrasion on the face, hands, or feet that could affect function or cosmetics.

Related Concepts and Next Steps

Healing an abrasion sits within the broader realm of wound management. If you’re curious, you can explore topics like burn care, cut and laceration repair, and scar reduction techniques. Understanding the differences between Burns thermal injuries that damage deeper skin layers and sometimes cause fluid loss and abrasions can sharpen your first‑aid skills. Likewise, learning about Chronic wounds wounds that fail to progress through the normal healing phases, often seen in diabetes helps you recognize when a simple scrape could become a larger health issue.

Bottom Line

While an abrasion may look minor, the body orchestrates a sophisticated healing cascade that can be supported with proper care. By cleaning gently, keeping the wound moist, and watching for infection, you give your skin the best chance to seal quickly and leave a faint scar at most. Remember, abrasion healing isn’t a race; it’s a steady process that respects your age, nutrition, and overall health.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does it take for an abrasion to fully close?

Most minor abrasions seal within 5‑7 days, while larger or deeper scrapes may need 2‑3 weeks for full closure. Complete remodeling of the scar can take several months.

Is it okay to use hydrogen peroxide on a fresh abrasion?

Hydrogen peroxide is too harsh for everyday use; it kills healthy skin cells and can delay healing. A gentle saline rinse is a safer first step.

Should I keep a scab on an abrasion?

A scab forms when the wound dries out. While it protects the area, it also blocks cell migration. Modern wound care favors a moist environment, so gently re‑wetting the scab with sterile saline and applying a thin ointment often speeds healing.

Can I use over‑the‑counter antibiotic ointment on any abrasion?

For clean, shallow scrapes, a simple petroleum jelly is sufficient. Reserve antibiotic ointments for deeper or contaminated wounds, and discontinue if you notice redness or itching that suggests an allergic reaction.

What signs indicate that an abrasion is infected?

Look for increasing pain, swelling that spreads beyond the edges, pus or a yellow‑green discharge, a foul smell, and fever. If any of these appear, seek medical attention promptly.

Do vitamins speed up abrasion healing?

Vitamin C aids collagen synthesis, while zinc supports cell proliferation. A balanced diet with adequate protein, fresh fruit, and vegetables can improve healing time, but supplements are only helpful if you’re deficient.

Health and Wellness

Health and Wellness

Mara Mara

September 27, 2025 AT 12:21Great rundown! The body really does a marvel of coordination, and knowing the phases can keep panic at bay. Keep those tips handy-clean, moisten, and watch for infection. It’s amazing how a simple saline rinse beats pricey dressings in most cases. Stay safe out there!

Jennifer Ferrara

September 28, 2025 AT 05:01While the exposition delineates the physiological cascade with commendable clarity, it is pertinent to acknowledge the epistemological underpinnings of wound management. One must consider the interplay between macro‑environmental factors and micro‑cellular dynamics, lest one neglects the holistic nature of healing. Moreover, the selection of antiseptic agents should be guided not solely by antimicrobial potency but also by biocompatibility, thereby averting iatrogenic impediments. In this vein, the author’s recommendation of petroleum‑based ointments aligns with contemporary best practices, albeit with the caveat that over‑application may occlude gaseous exchange. Definately, further discourse on the socioeconomic implications of dressing choices would enrich the treatise.

Terry Moreland

September 28, 2025 AT 21:41I totally get the anxiety when a scrape looks nasty. The step‑by‑step guide you gave is super helpful-especially the part about keeping the wound moist. I’ve tried the saline rinse myself and it really speeds up the pink phase. Just remember to change the dressing daily and keep an eye on any red streaks. You’ve got this!

Abdul Adeeb

September 29, 2025 AT 14:21The author’s articulation of the inflammatory cascade is, for the most part, accurate; however, a few lexical imprecisions merit correction. For instance, the phrase “blood vessels constrict to limit bleeding” should be accompanied by a subsequent vasodilation phase, which the text omits. Additionally, the term “scab” is employed without reference to its histological composition, which may mislead lay readers. Precision in nomenclature is essential for effective knowledge transfer. Overall, the exposition remains commendable.

Landmark Apostolic Church

September 30, 2025 AT 07:01The article hits the sweet spot between science and practicality-nothing too textbook, nothing too vague. I appreciate the nod to cheap home remedies; not everyone can splurge on hydrocolloids. Keeping it simple works for most of us.

Matthew Moss

September 30, 2025 AT 23:41Only the strong survive, so use proven antiseptics!

Antonio Estrada

October 1, 2025 AT 16:21I concur with the earlier points about moisture balance; a properly moist environment indeed accelerates re‑epithelialization. It might also be worthwhile to mention that over‑tight bandaging can impede perfusion, which is counterproductive. Collaborative efforts in sharing these nuances help the community grow.

Kevin Huckaby

October 2, 2025 AT 09:01Whoa, 🌟 that’s some solid science, but let’s not forget the old‑school hack-apply a dab of honey 🍯! It’s sweet, antibacterial, and totally badass for those stubborn scrapes. 😎

Brandon McInnis

October 3, 2025 AT 01:41What a comprehensive guide! 🎉 I love how it breaks down each phase with clarity, making it easy for anyone to follow. The tip about staying hydrated is a game‑changer; our bodies are literally built on water. Kudos to the author for demystifying wound care without overwhelming jargon. Keep the practical pearls coming!

Aaron Miller

October 3, 2025 AT 18:21While the enthusiasm is commendable, one must not succumb to pop‑culture embellishments masquerading as medical advice; the reliance on emojis, albeit engaging, can dilute the gravitas of clinical discourse. Furthermore, the assertion that hydration alone dramatically alters scar formation overlooks the complex interplay of systemic factors such as age‑related collagen cross‑linking and genetic predisposition. A rigorous, evidence‑based approach would supersede anecdotal optimism, ensuring that recommendations remain within the bounds of peer‑reviewed literature. In short, flair should never replace factual fidelity.

Roshin Ramakrishnan

October 4, 2025 AT 11:01First and foremost, let me welcome everyone into this constructive discussion about abrasion care; your contributions truly enrich the collective understanding. It is essential to recognize that wound healing does not occur in a vacuum-social determinants of health, access to clean water, and educational resources all play pivotal roles. For individuals in low‑resource settings, a simple saline rinse can be lifesaving, but even that may be limited by scarcity of sterile solutions. In such cases, boiled and cooled tap water serves as an acceptable alternative, provided the container is properly sterilized. Nutrition, as highlighted earlier, is another cornerstone; proteins supply the amino acids necessary for collagen synthesis, while vitamin C acts as a co‑factor for hydroxylation reactions that stabilize the extracellular matrix. Moreover, zinc supplementation has been shown to accelerate re‑epithelialization, yet it must be balanced to avoid copper deficiency. Smoking cessation cannot be overstated-nicotine constricts vasculature, starving the wound of oxygen and nutrients, thereby prolonging the inflammatory phase. Chronic conditions like diabetes demand meticulous glucose control, as hyperglycemia impairs leukocyte function and hampers angiogenesis. Equally important is the psychological aspect; stress hormones such as cortisol can suppress immune responses, delaying closure. Therefore, incorporating stress‑reduction techniques-whether mindfulness, gentle exercise, or supportive social interaction-can indirectly benefit the healing trajectory. From a cultural perspective, certain traditional remedies, such as aloe vera gel or tea tree oil, possess antimicrobial properties and may be integrated judiciously, respecting both scientific evidence and patient preferences. However, one should remain vigilant for potential allergic reactions, especially in individuals with a history of dermatologic sensitivities. In terms of dressing selection, the hierarchy of cost versus efficacy should guide choices: while hydrocolloid dressings excel at maintaining moist environments, they are not universally necessary for superficial abrasions. Simple non‑adhesive gauze combined with a thin layer of petroleum jelly often suffices, especially when change frequency is adhered to. Finally, ongoing patient education-empowering individuals to recognize signs of infection such as expanding erythema, purulent discharge, or systemic fever-is critical to preventing complications. By weaving together biomedical insights, socioeconomic awareness, and compassionate guidance, we can ensure optimal outcomes for all wound sufferers.

Todd Peeples

October 5, 2025 AT 03:41The preceding exposition adeptly integrates pathophysiological mechanisms with sociocultural determinants, thereby exemplifying a systems‑biology paradigm. From a mechanotransduction viewpoint, the extracellular matrix remodeling phase is modulated by integrin‑mediated signaling cascades, which are susceptible to hypoxic stress induced by tobacco exposure. Consequently, the recommendation to discontinue smoking aligns with the attenuation of hypoxia‑inducible factor (HIF-1α) activity, fostering angiogenic proficiency. Additionally, the incorporation of nutraceuticals such as ascorbate and zinc engages the collagen‑hydroxylation enzymatic axis, enhancing tensile strength. While traditional botanicals may confer adjunctive antimicrobial effects, rigorous randomized controlled trials remain requisite to substantiate their clinical utility. Overall, the synthesis of evidence‑based practice with patient‑centered education constitutes a paradigmatic approach to wound management. 🌟